Primates and bacteria fighting for iron for 40 million years

Bacteria need iron to live. Therefore, an antibacterial defense mechanism is the non-availability of iron. This is effective until bacteria get some mechanism to get this iron. Well, in this fight for iron, primates and bacteria have been around for at least 40 million years, according to a recent paper published in the journal Science.

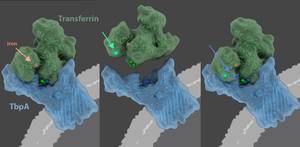

Iron in the blood is carried by a protein called transferrin, which prevents iron from being free in the blood, accessible to bacteria. However, some bacteria, such as meningitis and gonorrhea, have developed a weapon to fight it: Protein called tbpA. This protein binds to transferrin and extracts iron.

Two researchers at the University of Utah have studied the transferrines of 21 primates and the Tvd of several bacteria, and have discovered that these two molecules have undergone many changes for 40 million years. In the case of transferrin, they have seen that virtually all changes have occurred in one of the two lobes containing it, the lobe to which the Tvd is associated. And by checking when changes have occurred, they have found total parity between primates and bacteria. Thus, researchers conclude that these changes correspond to an evolutionary struggle. That is, after a change in the transferrin to escape to the Tvd, there has been a new change in the Tvd to be able to extract iron back to the transferrin. And so on for 40 million years.

On the other hand, they observe that with a last change that has suffered the transferrin, the bacteria have again avoided its detection. Today, a quarter of the world's people have this latest variant of trasferrina.