Current techniques, the key to understanding the past

Cave art research begins with data collection. Diego Garate and Joseba Rios have explained that the first thing they do is to systematically explore the walls and ceiling of the cave. "In this lighting is very important and with some current lanterns it is like the sun inside the cave," said Ríos.

However, Garate recalls that experience and meaning are essential elements: "Ascension is a good example. Askondo is located in Mañaria, in Bizkaia, and those around him have always known it. But no one paid attention to the red paintings at the entrance until we were."

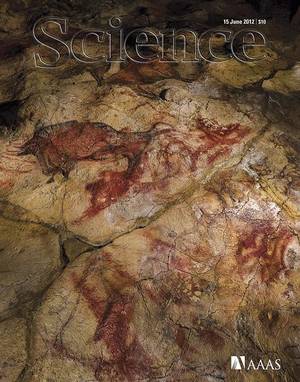

In 2011, Joseba Ríos, Diego Garate and Ander Ugarte found the paintings: ten horses, one hand, the back of an animal, one point, some stripes, an engraved horse and a recessed bone. "But we wouldn't notice either if we hadn't seen a thick layer of calcite on the paintings. Thanks to this we realized that what was underneath should be old," they confessed. So, although they are still under study, they know that between 28,000-20,000 years ago. The bone, for example, has already been dated and has seen that it is approximately 23,800 years old.

Everything found is collected in standard sheets, both quantitative and qualitative, and is not limited to graphic representations, but it is very important to properly collect the environment, also record compositional and topographic information.

It is complemented by the elaboration of graphic documentation through photographs and drawings. In this sense, advances in photography have been fundamental to capture quality images such as the use of macro to capture details.

In addition to photographs of the details, they take photographs of the entire image, the group and the environment. "However, we must not forget that we are inside the cave, in an uncomfortable place, perhaps lying down and almost glued to the wall, with little space to take the photo...", warned Ríos. That is, in addition to a good team, archaeologists must master the technique.

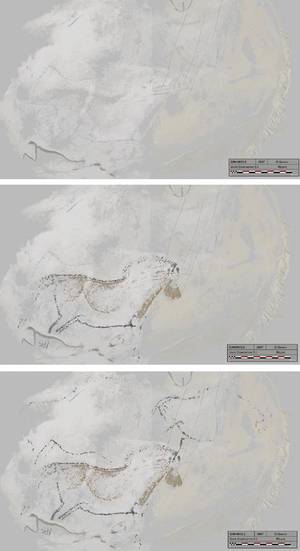

In addition, they now use ultraviolet and infrared light to take pictures. This way, in some cases they get other information, for example, one of the horses that appear very blurred in Askondo looks much better in the multispectral photo.

Computer and manual

In any case, Ríos and Garate give drawings as much or more importance than photographs. In fact, as explained by Garate, "how you put the light, in the photos appear the shadows and the relief is lost. In the drawings we can collect everything."

For example, it is very important for archaeologists to collect the order of the images, since in one place there are paintings of different times, often overlapping. "We make the decals of each epoch and we order them chronologically. In the end it's creating infographics."

The images collected are treated. Some do everything digitally, but Garate and Ríos prefer mixed media. Thus, with the images treated on the computer they return to the cave and draw them on them to complete the image. Then they scan it, treat it again, go back to the cave... According to Ríos, "to make a single image, perhaps we have to go back to the cave 5 or 10 times."

According to them, in most cases, only through photographs and without leaving the laboratory, "it is impossible to make good decals". In addition, you have to collect the relief and appearance of the wall, "and for this you have to make a lot of layers", explains Ríos.

In all cases, they don't even touch the images on the wall. "Before, to make decals, some placed the decal paper on the image and painted it on it. Of course, this risks damaging images. And even more harmful things have been done, such as making silicone molds that have unintentionally carried parts of the wall." Archaeologists now prioritize image maintenance.

In addition, currently they have the possibility to use the laser scanner. This shows very precise 3D images of the cave. "Until recently we didn't have it and it's an incredible breakthrough. In recent years, it has become much cheaper," said Garate. "The 3D images of the cave offer other information about the paintings: from where it gave the light, what the whole environment looks like, what place they chose to make the paintings..."

Based on samples

Archaeologists not only act in the cave and in front of the computer, but also in the laboratory. The samples collected from the wall are analyzed there. "So we get a lot of information. For example, if the paint is coal, we can take a small sample of coal from the wall and use the microscope to know which trees that piece of coal belongs to. And the carbon-14 test can be done. Before this, the pigment must be identified with inorganic (manganese, iron...) ), you can't use carbon 14," warns Garate.

The dating can be direct or indirect. Rios explains the difference: "In direct dating a sample of the painting is taken and the date of its realization is determined. In the transversal we date the material that has below or above the paintings and we know that it is older or younger than him. It is not accurate, but sometimes there is no other way to calculate the age of the paintings." However, they have recognized that direct dating, such as carbon-14, is also problematic, as samples can be contaminated, for example.

Other analyses are performed with mineral pigments. For example, they analyze the origin of the paintings and their mixture, compare them with the pigments of the paintings of the walls and nearby caves... The goal is to get as much information as possible without destroying the paintings.

Organize, process

Once all the information is collected, the next step is to organize and process the data. They study the typology of paintings (silhouette, details, proportion, animation, perspective...).

Archaeologists Garate and Ríos have clarified that this study has nothing to do with the chronological system of Leroi-Gourhan. "When analyzing the typology, we intend to see what similarity or singularity have certain characteristics of the paintings with respect to those of a place, if from it we can draw conclusions. For this, we use statistics, because it is useless to say, most have a similar appearance. Most are not objective data, 70% are objective," explains Ríos.

Statistics also help analyze the location and spatial distribution of images. Garate explains: "We look at where each image is and where they occupy each other. In fact, they often made some figures over others. This seems to indicate that perhaps the most important thing is not the painting itself, but the place, that piece of wall they have chosen to paint. On the other hand, it seems logical to think that the images found in the public place, for example, at the entrance of the cave, and at the bottom of the cave, would not have the same function or meaning in a hidden and elevated place."

Apart from the statistics, the microscopic study helps them to know the whole process of making the image: what pigment and technique they used (continuous stripe, dotted, blown...), how useful they did it (brushes, hands, fingers, burnt bones...), where the stripe begins and ends. "It is noteworthy the diversity that exists; they did everything," says Ríos.

And other methods, such as ethnography and experimentation. In fact, according to Ríos, experimentation can help a lot in some cases. "It's not enough to say they did so; if you do the same, you can be safer."

Not only answer

Archaeologists have much more information about rock art than before. In addition, thanks to archaeologists who research other fields, Ríos says they have more information about their authors: "Garate is specialized in the research of rock art, and I investigate aspects related to the life of the Palaeolithic man: his environment and way of life, his tools... The two spaces are complementary, so we understand rock art and its era much better."

Of course, they do not have a unique and secure answer to the usual question: what role did those images play? Moreover, Ríos has advanced that "wrong" is to interpret all equally and think that all had a single function, "especially considering the wide chronological range they occupy, the wide geographical field in which they have been exposed and the different characteristics they present."

"Moreover, we know only those who have survived to date and those we have found, and everything else is unknown to us. We know very little about the context, so it makes no sense to seek a single interpretation," added Garate.

However, for many years experts have tried to give a single interpretation. XIX. In the 19th century, for example, the most accepted theory was that of “art for art”, which they drew because it makes them want. But, according to Garate, it is not credible: "If this were so, they would draw anything and the themes would not be repeated over and over again."

Other explanations that have been given over time are totemism (consideration and worship of an animal as ancestor of the group), sympathetic magic for hunting or reproduction and sexual dichotomy (animals representing the female and others the male). The three have also been rejected by the numerous contradictions that have been presented for approval.

The final interpretation is Xamanism. This is defended by the prestigious archaeologist Jean Clottes, UNESCO expert. In his opinion, these images are made by shamans, intermediaries between reality and the spirit world. However, Garate and Ríos are unclear that this is the explanation: "Today there are shamans who, to relate to spirits, take certain substances. The truth is that the images and signs they make when they are under their influence are not real, and most examples of Paleolithic art are very real."

In short, Ríos and Garate believe that interpretations can be very varied. Proof of this is the following example: "If we look at the area we can see a lot of animal figures: a bear in a t-shirt, a bull in a bottle, a sheep stuck in a car or a pig in a spoon. And we don't try to give the same explanation to everyone."