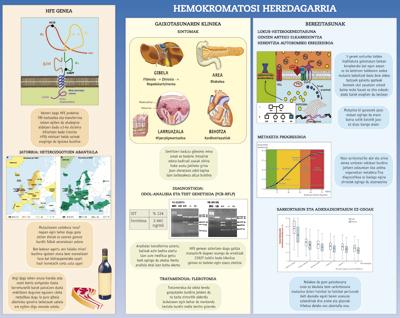

Hereditary hemochromatosis in verses

One in two hundred inhabitants of western countries suffers hereditary hemochromatosis, the most common genetic disease in our society. As a consequence of this disease there is a progressive accumulation of iron in the body, first in the blood (the word hemochromatosis means "colorful blood" because iron darkens the blood) and then in the tissues. The damage is more premature and severe in men, since women, due to the loss of blood from menstruation, have a slower and delayed accumulation.

Hereditary hemochromatosis is the result of incorrect regulation of iron metabolism. This regulation is directed by the liver thanks to proteins located in the plasma membrane of hepatocytes. When blood iron levels are high, these proteins form a regulatory complex and cause the synthesis and secretion of the hormone hepzidine. This hormone will be responsible for avoiding the absorption of iron in the intestine and thus recover the adequate level of iron in the blood.

Mutated gene from any component of the complex can produce hereditary hemochromatosis. But the main agent is the mutation of the HFE protein. Two main mutations can occur in the HFE protein: H63D (no significant influence) and C282Y. As a consequence of the latter, the structure of the FEP changes radically and cannot be integrated into the plasma membrane of hepatocytes (regulatory complexes are not formed). This mutation produces 85% of hereditary hemochromatosis.

Why is the mutation so widespread? It seems that the explanation is the advantage of heterocycats, which do not develop the disease, but have higher than normal iron levels. It is estimated that the C282Y mutation appeared in Ireland 2,000-3,000 years ago, when the diet of that time was very low in irons, which caused serious problems. Thus, the “error” that guaranteed higher iron levels was a gift that was passed down from generation to generation. Now that we have many foods rich in iron, this legacy that our ancestors have handed down to us has become an enemy.