CAF-Elhuyar 2018: Basque Country Mountains: a landscape carved by large herbivores

When we imagine landscapes prior to the agricultural dispersion in Europe or are represented in films or documentaries, endless closed jungles usually appear. It seems that the open and grassland landscapes emerged with human intervention, with the aim of exploiting the wood and feeding the animals. However, the evolution of the European landscape has been much more complex and the role of the great herbivores has been fundamental both before and after the arrival of agriculture.

Evolution of open habitats

To understand the current configuration of the Basque landscape, it is necessary to look at the geological phenomena of the last millions of years. About 35-25 million years ago, in the middle of the Cenozoic Age, the movements of continental plates provoked the alpine orogenesis, process in which the Cantabrian mountain range, the Pyrenees and the arc of the Basque Country was formed. The new configuration of the continents caused changes in ocean circulation that reduced atmospheric CO2 concentration and global temperature. In these new conditions, pasture ecosystems were extended in areas with seasonal drought conditions [1].

In the last 12,000 years (Holocene), the extent of open habitats has suffered numerous fluctuations in Europe. However, it seems that these habitats remained fairly stable before the arrival of agriculture, without falling from 12-30% of coverage. The European landscape was, therefore, mosaic, as open habitats and forests alternated [2]. Wild herbivores directly influenced this configuration of the landscape, since they maintained open forests in which wild horses [3], deer, deer, uros, European bison...

Creation and decline of the seminatural landscape

When the peasants expanded through Europe from the Middle East (about 7,000 years ago) primary forests were cleared and the original wild herbivores were replaced by domesticated animals. The process was gradual, for example, documentation of the last bison hunted in Navarre XII. Dependent.

Although, with the arrival of the peasants, much of the landscape was altered, the majority of the species that formed pastures and scrublands were already present in open habitats of origin.

Profound changes XIX. They arrived in the mid-twentieth century. Agricultural mechanization and the massive use of pesticides created in Europe a current landscape of intensive cultivation. The man caused profound changes in the flora and fauna: several species disappeared and numerous exotic species were introduced.

Since most wild herbivores have now disappeared in Europe, practically all of the remaining pastures of high conservation value are associated with extensive grazing systems [4]. However, these systems are in decline with the eviction of rural nuclei. The situation of the mountains of Euskal Herria is no other, since the use of mountain pastures gradually decreases in their pasture systems [5].

Key functions of herbivores

The herbivores, in addition to modeling the landscape, fulfill a series of key functions in ecosystems. Grazing is of vital importance for the survival of species linked to open habitats. In the same way, grazing directly affects the different processes of the ecosystem through defoliation, tread and deposition of urinary feces, such as food recycling and pasture production.

_galeria.jpg)

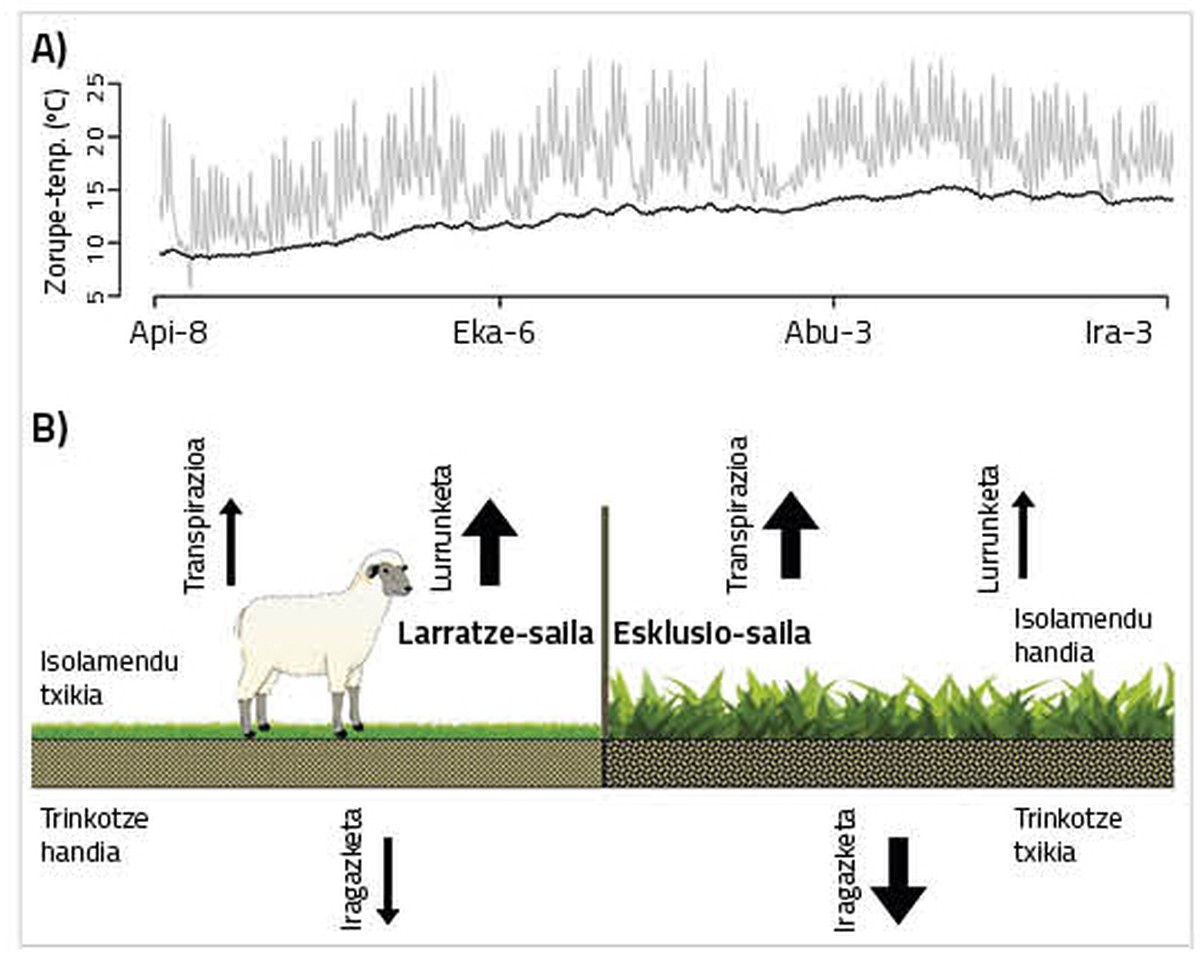

The general objective of my doctoral thesis is to better understand the consequences of the interruption of mixed grazing (ovine, bovine and mare) in these grazing functions. For this purpose, the abandonment of grazing in four experimental areas of the Sierra de Aralar was simulated. Construction of enclosures that avoid the entry of cattle (figure 1) and comparison of the evolution of the grassland for 13 years (within the enclosures) with the maintenance of the grazing (outside the enclosures).

Grazing and functioning of ecosystems

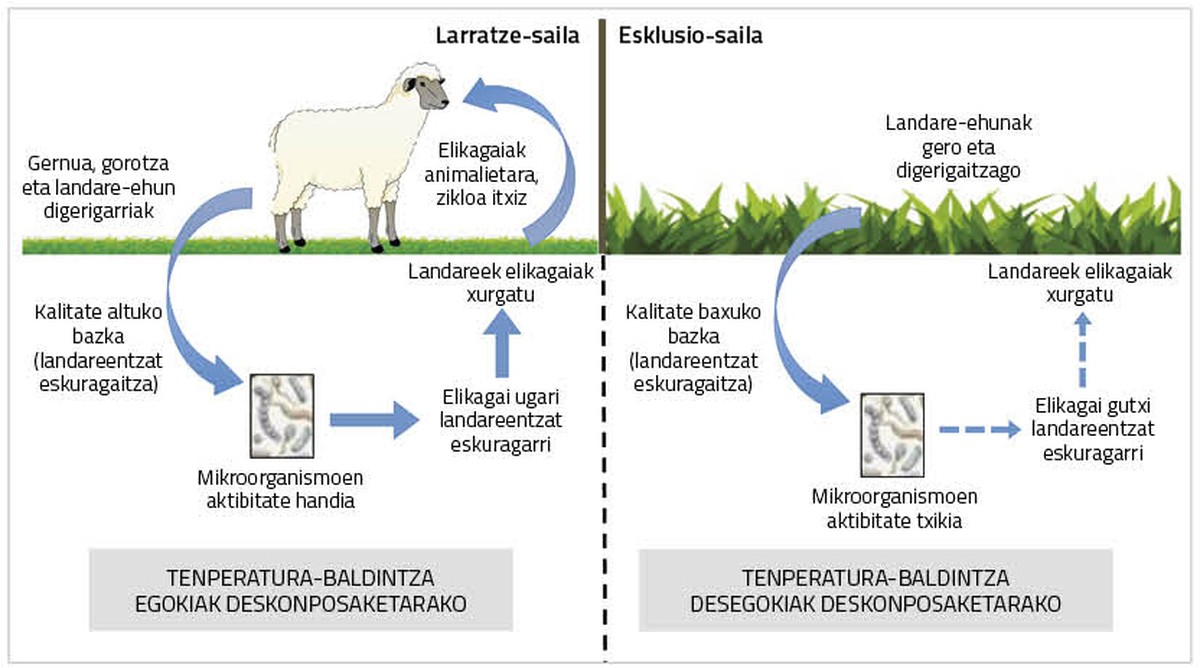

Grazing affects the activity of terrestrial microorganisms (bacteria and fungi), the food cycle and the availability of food [6]. On the one hand, herbivores fertilize the grassland with the feces and with the defoliation they perform when eating grass, they promote the regeneration of the plants. This regeneration keeps young plant tissues, which facilitates the digestion of fodder. On the other hand, herbivores deeply affect soil temperature and water content and, therefore, soil processes [7]. In my thesis, to analyze the influence of the abandonment of the grazing of the animals in the mountain pastures, the temperature and water content in the subsoil were measured in the plots in which animals have been grazing and has not been grazing. Likewise, the quality of the herb (nutritional value and digeribility) was measured in both conditions. Digestibility is the relationship between the most digestible cell wall fibers and the most digestible cell content proteins.

The consequences are clear, the soil temperature conditions are very different in the grazing areas of the animals (grazing areas) and in the non-grazing areas (exclusion zones). Temperature variations are much higher in the grazing sections: daily incidences in the grazing sections are similar to annual fluctuations in the exclusion categories (Figure 2 A). This is because the herbivores maintain the short grass layer. This makes the air temperature changes have an immediate incidence on the subsoil. In contrast, in the exclusion section there is a thickening of the herbaceous layer, so the subsoil is kept more isolated. For the same reason, in spring-summer the temperature of the subsoil increases in the grazing areas. Grazing also affects the water content in the subsoil (Figure 2 B); being a thinner layer of insulation, there is a higher loss of water by evaporation in the grazing areas. On the other hand, the compaction of the soil by the animals that graze in the plantations reduces the size of the pores of the soil, increases the water retention capacity and reduces the loss of water by filtration. In addition, the increased maintenance of plant biomass in the exclusion series makes vegetation transspire more and more water is lost to the atmosphere. These complex relationships make the water content to remain higher in grazing areas when solar radiation is low (cloudy environment) due to low evaporation. On the contrary, the consequences are adverse when the solar radiation is high (sunny environment), since much water is lost by evaporation in the grazing areas. In any case, Atlantic grasses are very rainy and water scarcity is not a serious problem for the operation of the grassland. In addition, it must be taken into account that the quality of the grass is higher in the grazing plantations.

These changes have consequences in the food cycle (Figure 3). Combining the highest temperature of the grazing areas with a better forage quality, the microorganisms present in the soil accelerate the decomposition of the plant residues. Therefore, food is left loose on the ground so that plants can reabsorb, and finally, herbivores retake food when they eat grass. This closes the cycle. The alternate temperature also accelerates the decomposition process and favors this cycle. However, if we remove the herbivores from the puzzle, the temperature becomes lower and stable. In addition, the regeneration of the grassland is not encouraged, and the food becomes more digestible. Its combination reduces the activity of soil microorganisms and begins to concentrate food on the soil in complex structures inaccessible to plants. The consequence is that the food cycle slows down and damages the functioning of the pasture.

Grazing and biodiversity

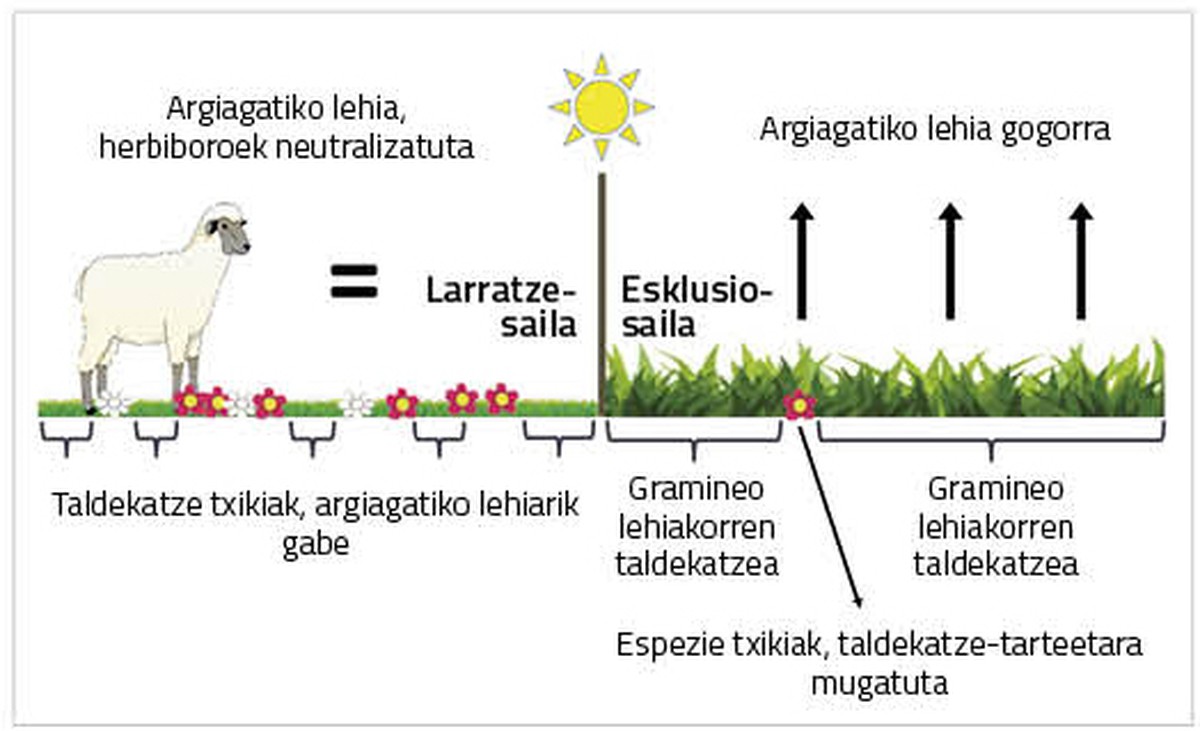

The general model of grazing indicates that in fertile pastures like those of Aralar the diversity is low in low intensities of grazing, the highest in average intensities and descends again in high intensities [8]. Without herbivores, the plants have no limits of growth up and the competition for light is very hard. Consequently, few highly competitive species gradually discard the rest, reducing diversity. On the contrary, when the intensity is very high, soil degradation and erosion problems occur. Also in this case, only species adapted to these harsh conditions survive and diversity is lost. The average intensities are the ones with the highest diversity: on the one hand, because the competition for light is softened and, on the other, because most species are adapted to moderate levels of alteration.

To test the hypothesis mentioned above in the pastures of Aralar, a very local scale (20 m x 20 m of surface) was described the composition of species of the grassland, both in the areas where animals have been grazed and in those that have not been grazed. In this small scale, the sampling was carried out, since the interactions between plants are given on a local scale. It was observed that in the plantations where there were no herbivores, a few gramineae, capable of reaching a great height, produce large groups that progressively discard smaller species. For these small species it is impossible to include them in the groups that form the grasses, since the competition for light is very hard. These species are necessarily limited to intermediate spaces of increasingly large groups until their extinction. Thus, the diversity has been reduced in the plots in which there have been no herbivores: in the grazing plots there have been counted between 29 and 37 species, and in the exclusion plots between 19 and 28 species, after 13 years of exclusion (Figure 4).

Reflections for management

In this thesis it is observed that the sustainable management of traditional livestock is fundamental for the conservation of mountain pastures. The functioning and diversity of grasses is maintained in a balance developed over thousands of years, while the presence of herbivores begins to experience profound changes shortly after conditions changed.

Finally, there are other interesting ideas in the world to respond to the eviction of rural areas. For example, in the Dutch natural space of Oostvaardersplass: before the declaration of the reservation, the natural space was a nursery of willows and, once abandoned the activity of the seminar, they realized that there were hundreds of willow buds per square meter. Aware that the arrival of the confined forest would make the habitat of aquatic birds disappear, the park's administration restored a community of wild herbivores that naturally has managed to create a landscaped mosaic of wooded grasslands in a few years (Figure 5).

Can you imagine bison grazing on the mountains of Euskal Herria?

Bibliography Bibliography Bibliography

[1] Tallis, J.H. 1991. Plant Community History: Long-Term Changes in Plant Distribution and Diversity. London. Chapman & Hall.

[2] Hejcman, M., Hejcmanová, P., Pavlu, V., Benes, J. 2013 Origin and history of grasslands in Central Europe – a review. Animal Production Science 41: 1231-1250.

[3] Vera, F.W. 2000. Grazing Ecology and Forest History. CABI, Wallingford, UK.

[4] Bignal, S.L., McCracken, D.I. 1996. - Journal of Applied Ecology 33: 413-424.

[5] Ruiz, R., Day-Unquera, B., Beltrán de Heredia, I. Mandaluniz, N., Arranz, J., Ugarte, E. 2009. The challenge of sustainability for local breeds and traditional systems: dairy sheep in the Basque Country. Proc. of the 60th Annual Meeting of the EAAP, TN WAP. Barcelona.

[6] Bardgett, R.D., Wardle, D.A. 2003. Herbivore mediated linkages between aboveground and belowground communities. Ecology 84: 2258-2268.

[7] Schrama M., Veen, G.F.C. Bakker, S.L. Ruifrok, J.L. Bakker, J.P., Olff, H. 2013 An integrated perspective to explain nitrogen mineralization in grazed ecosystems. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 15: 32-44.

[8] Milchunas, D.G., Hall, VºBº, Lauenroth, W.K. 1988. A generalized model of the effects of grazing by large herbivores on grassland community structure. The American Naturalist 132: 87-106.