Thinking of Richard Feynman

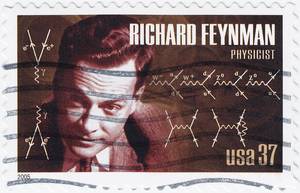

XX. In the 20th century, 161 people received the Nobel Prize in Physics. The life and work of some have gone beyond physics: Albert Einstein and Marie Curie, for example, are examples and icons of current scientists. However, many of the Nobel laureates are forgotten, they are only known because their names have been subject to a law or an equation. But there is an intermediate group whose names have not seduced the whole public, but they have not remained alone in the memories of the physicists. One of them is Richard Feynman.

UPV/EHU physicist Fernando Plazaola and the Vice-Rector for Research see his image as: "Richard Feynman, a highly successful scientist and disseminator, as well as being one of the greatest post-Einstein scientists. However, what I have learned most from this Nobel Prize is that scientific problems do not have the only solution. He, in a very effective way, tried to liberate the problems already liberated from new paths, opening up new ways of understanding nature that today are very successful."

He was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1965 for his research on quantum electrodynamics. It was a great work and of great impact; today, all particle physics researchers use the Feynman diagrams, a type of representation to communicate the creation, evolution and death of any particle smaller than the atom. They are used to explain the discovery of the Higgs boson.

He is a highly appreciated character in the world of physics. Pedro Miguel Etxenike, director of DIPC, says: "On the one hand, depth, and on the other, clarity and simplicity, because it combined both liked both theoretical and experimental physicists."

His lectures gathered many people. Moreover, the collections of some of these talks were published in book format, Six Easy Pieces: Fundamentals of Physics Explained and The Meaning of It All, for example, are not the only examples. The material created by Feynman has also been successful enough to translate into many languages.

Radios and atomic bomb

At the age of 11 Feynman became famous because in the neighborhood he "arranged the radios thinking." The anecdote is curious, a neighbor's radio did not work and Feynman nodded. The device had two valves and what had to be started when turning on the radio cost a lot of heating. The other worked well. To find him, Feynman carried out several tests with the radio, and after each one of them, it was thought to understand the situation. The radio owner was nervous. "What are you doing? ", and Feynman answers: "I'm thinking." He finally exchanged the two valves and repaired the radio. These were difficult times, since it was 1929, and the child began to take advantage of the idea.

After all, Feynman was following his father's advice that people would not listen to what he was telling him, but that, to solve a problem, he would look and understand the situation closely.

However, Feynman did not always follow this advice. In 1945 his first wife, Arline Greenbaum, died of tuberculosis. At first the doctor did the diagnosis well. But this was not conventional tuberculosis, and over time this diagnosis was ruled out in favor of lymphoma and Hodgkin's disease. Feynman read all he could about diseases and until it was late he did not realize that the first diagnosis was correct. Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman! In the book, Feynman says that if they had studied it correctly from the beginning, they would not rule out the first diagnosis. Instead of looking and understanding, they began to look for new theories. -Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman, who popularized Feynman's life. recommended book

At the death of his wife, Manhattan worked on the secret atomic bomb development project. There, in addition to the work, Feynman left a strong character and light footprint. It was a very secret project: many workers did not know what the final objective of the work was; they did mathematical calculations (because there was no computer) and made many mistakes. Feynman convinced the military directors of the project to communicate the objective to the employees and, when they did, increased the degree of employee involvement and greatly decreased the number of errors in the calculations.

Pope of nanosciences

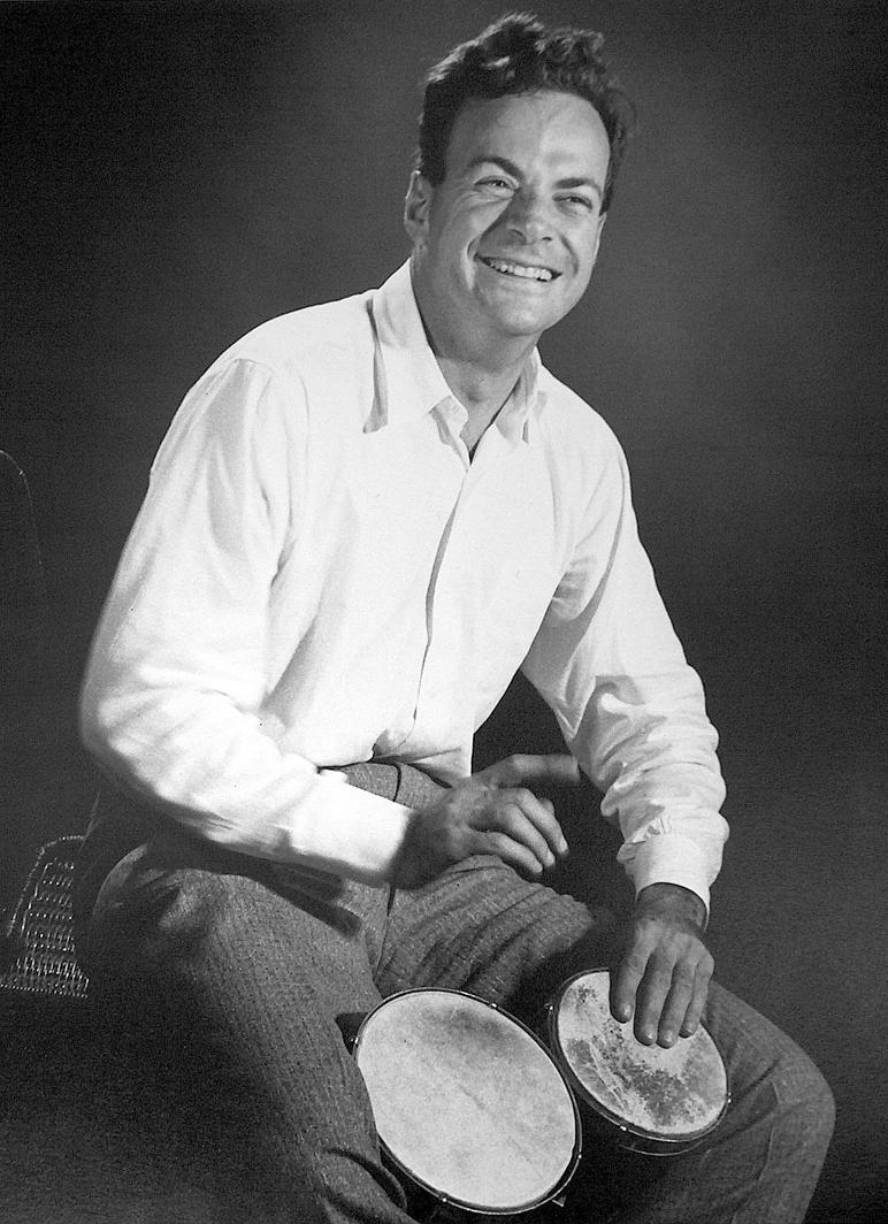

Feynman married twice more. His biography was very turbulent. He was a cheerful and surprising man. After researching the most difficult theories of physics, he left the university and went to touch the bongos, specifically, the photo of the Feynman became an icon in the twentieth century. between physicists of the twentieth century. He looked at nature wanting to understand things. Sitting in a bar, he took a handkerchief of paper and devoted himself to solving a problem; he defined himself as a naughty person, fond of jokes and especially curious.

In the summer of 1960 he worked in the laboratory of biologist Max Delbrück, at Caltech. There he researched the ribosomes; he wanted to know if the ribosomes are universal structures, that is, if the ribosomes of one species work well in the cells of another species. The answer is yes, although Feynman did not find it. But in that work he discovered a procedure to solve a mutated gene, medium of a second mutation of the same gene.

Ribosomes are fascinating nanostructures of nature. For Feynman they were a reference. In fact, he considered them exemplary in a lecture he gave in 1959. He referred to nanotechnology, although he did not use this word. DIPC physicist Enrique Ortega, an expert in nanotechnology, knows Feynman and the conference very well: "Among the physicists, Feynman has been greatly admired. Deserved, no doubt. He entered our life in the 1950s with the conference There is plenty of room at the bottom. In fact, his miraculous predictions at this conference became reality when the first discoveries of nanoscience and nanotechnology were made. But were they magical predictions or privileged information? More than the two, because he supposedly knew the process of miniaturizing microelectronic devices in U.S. industrial laboratories (IBM and Bell mainly). At that time, multilayer systems and the first quantum wells were developing, and Feynman knew the consequences this would have. Therefore, some of the predictions of this conference were not really the original ideas of Feynman, but also of other members."

End of life

The Nobel Prize announcement came one night to Feynman within hours. In Sweden it was announced by day, of course, but in the United States it was still night. Feynman was sleeping, a journalist called him to give him the news and get the first words, but all he got was Feynman's rebuke. It was not time to phone.

The award made Feynman's life more complicated. He received thousands of requests to deliver the talks. All Nobel laureates receive these requests, but Feynman's case was special. It was not like any other Nobel prize. Not only did he work in prestigious universities: MIT, Princeton, Cornell and Caltech. He was also a great communicator and very good teacher. In fact, when he was offered high-level jobs, Feynman chose Caltech's, since among the roles of the position was teaching.

This reputation brought Feynman a last major job. In 1986, NASA's Challenger ferry exploded 73 seconds after takeoff. NASA gathered a committee of experts to clarify the reasons for the accident and, among others, called Feynman. The physicist had a hard time overcoming the protocol, escaping the counselors and talking to simple engineers. But he got it and made a surprising contribution to the work of the commission. The Commission agreed that the accident was a very unlikely event, but Feynman disagreed and did not sign the final report. He discovered that it was not so and managed to add an explanation in the report in an annex. More errors in ferry flights confirmed Feynman's theory.

Richard Feynman was a special man. He was a charismatic, intelligent, fun person and, according to a classification published in 1999 by the journal Physics World, one of the ten largest physicists in history. Clearly his prestige has surpassed the Nobel. -Listen to the fire Richard Feyman in the program Norteko Ferrokarrilla.