Pompeii: what it was, what it seems and everything, at the hand of chemistry

Maite Maguregui Hernando, a member of the UPV-EHU research team and a PhD in Chemistry, has spent ten years researching the frescoes of Pompeii. Remember how a team from here started working at the Pompeii site: “We met a Finnish woman, the very chemistry of the Metropolitan University, who showed great interest in the methodology with the tools we used. Thanks to him we went for the first time to Pompeii”.

In fact, they use portable tools to perform analysis. Methodologically they are not limited to the analysis of pigments, mortar and other elements, but they try to clarify how they were in origin and how and why they have degraded. The Metropolis researcher worked with the EPUH archaeological team in Pompeii and spoke with them to get Maguregui's team out there.

Thus, in 2008 small samples of mural painting were collected. They were analyzed in the UPV-EHU laboratory and the results were “very satisfied”. A scientific article was also published in 2009 with the publication of this research.

Invitation to investigate in Pompeii

It was Maguregui's final thesis work, so it was so special for him to receive the invitation to Pompeii to investigate the following year: “It was exciting. Then you get used to it, but on that first occasion, for example, I remember that I was very excited to see how little we have advanced. Because the houses, the streets... We still have those things, even the zebra steps!”

House of Marcus Lucretius, the house of Marcus Lucretius. The excavations of Pompeii began approximately in 1850, and for almost 170 years this house was excavated, but on the banks there is still the unexcavated area, which was the objective of the archaeologists EPUH. “At first it was about investigating the nature of pigments, but when we went there we saw that there was a lot of work to do,” explains Maguregui.

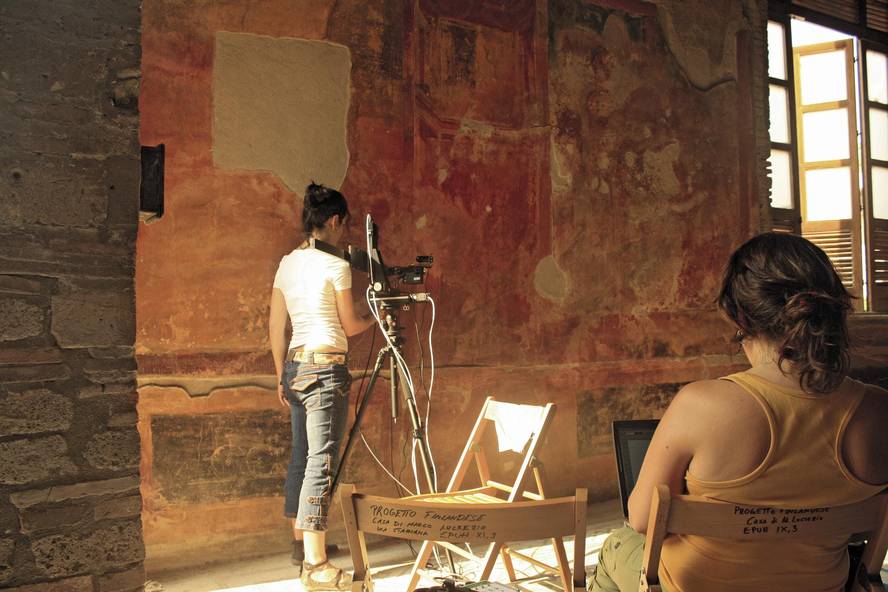

Since that first year management has changed, which has affected the way the work is done. At first, only researchers could access the site of Pompeii. However, the following year, thanks to a grant from the European Union, an ambitious research and protection project of Pompeii (Grande Progetto Pompei) was launched, which since then is a stricter and registered control. Sample collection permits have also been reduced, so their portable tools are essential for obtaining information in the archaeological area itself. This imposes some work limits, but at the same time Maguregui values positively the conservation and restoration criteria adopted by the Archaeological Park of Pompeii.

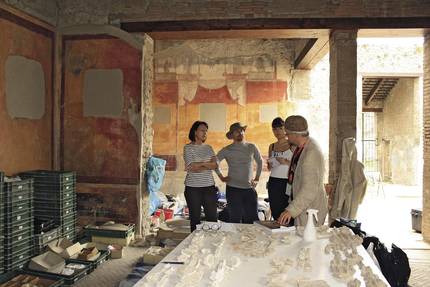

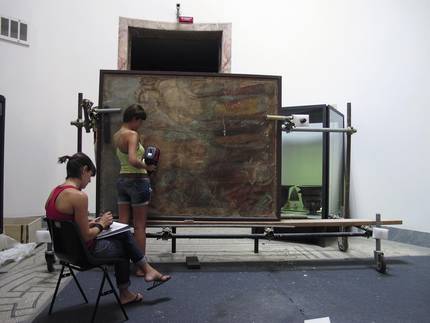

With the creation of the APUV project (Analytica Pompeiana Universitatis Vasconicae), three campaigns were conducted at Marcus Lucretius' home between 2010 and 2012. Ten researchers from the IBeA group are currently participating in this project. The group's work consisted of analyzing the mural paintings. This is how Maguregui summarized his work: “In the Roman houses there was a living room, the triclinium, in which were the most spectacular and elaborate mural paintings. However, in the houses excavated in the past, it is customary that the most spectacular images of the murals that were detached from the walls are missing and taken to the Archaeological Museum of Naples. We were fortunate to be able to attend the museum. Thus, we analyze the footprint of the mural painting that is currently preserved in the wall and the part extracted from it.”

According to him, it was very interesting to see how the current atmosphere affects these materials, since the fragments found in the museum are much better preserved. “In addition to studying the pigment, we characterize the mortar. In fact, pigments are applied on it, which also suffers degradation: salts, biocolonizations can occur... So we were able to analyze the differences between the evolution of pigment and mortar in the site and in the museum’s warehouse.”

In 2012, archaeologists completed the work of Marcus Lucretius, and the work of the IBeA group was completed. A while later, however, they met a team from the University of Valencia who was researching in Pompeii and proposed to collaborate. Thus, Ariadna went home in 2014, where they analyzed their pigments and materials.

Fortune

And once again Maguregui confesses that luck accompanied them: “Right there, we got a visit. The case is that inside Pompeii there is a laboratory where the materials extracted from the site are located. They have minimal equipment to do some basic research, and when they saw us they surprised us with our tools and work. Then they told us they would talk to the main site manager in the area, and so we got the invitation to sign an agreement.”

Thus, in 2015 an agreement was signed between the UPV and the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, which allowed them to know a third house: Casa degli Amorini Dorati or house of the golden cupids, on the wall of the owner's room, in a glass discs coated with gold that will inscribe the image of the cupid. And today they are still in the same house, despite the fact that the agreement was valid until 2017, now they have renewed it until 2020.

According to Maguregui, it is very interesting because this house is open. “The visitor sees us working and it’s nice, at the same time we do outreach. We have posters with information and ask us questions. We know people of all kinds and places, including chemists, and enriching conversations are created.”

Tools and techniques

They are tools that use one of the aspects that arouses the attention of the public and not only of the visitors: Pompeii researchers also showed interest in them from the beginning and, to some extent, thanks to them are the members of IBeA. Maguregui explained that, in the world of art and conservation, they have to use non-destructive techniques, such as those of IBeA: “We use spectroscopic techniques and some devices, for example, are pistol shaped or similar and work supported on the wall. We don’t need to take samples and the tools leave no effects on the surface.”

Their methods are elementary and molecular. “We combine the data obtained with both. For example, if we observe with elementary techniques the presence of calcium and sulfur, later, by molecular techniques, we can observe the presence of plaster in the study area. Or with pigments like cinnabar, a red pigment, is mercury sulfide. We see, therefore, with elementary techniques mercury and sulfur, and with molecules, how these elements are structured at the molecular level.”

Evolution of pigments

This allows to know the current state of pigments. As for its evolution in time, its relationship with the Archaeological Museum of Naples has been of great help since they have been able to analyze the original pigments containing: “In the excavation were discovered the crushed pigments, the pigment powder, the ceramic bowls contained. So, we have analyzed the whole pallet of the time: red, yellow, green, blue... They were mainly red and yellow, with black and white. Then, to make more spectacular details, blue and green were used. Finally they also used pink, but only occasionally,” explains Maguregui.

In fact, they developed a methodology to determine the nature of the dyes used specifically to obtain pink: “We saw that the dye was extracted from the roots of a special plant, cooking the roots. In fact, at that time this color was also obtained from the inside of some shells, but in the pigments studied the same was not found, but the derived from the roots”.

Maguregui clarifies that the rest are of mineral origin and earth pigments: “For example, reds and yellows are lands, many of them with remnants of volcanic minerals. Moreover, when we analyze the volcanic lands of the deposit, we not only look at the pigments, but look at their influence. The eruption had notable consequences in the paintings.”

From yellow to red

Example of ochre pigment. Yellow ochre is a soil pigment that, according to its composition, is dehydrated by heat action. Thus, when the erupted material hit the walls, the temperature caused the yellow ochre to dehydrate and turn red. That is why, even though today there are more than two hundred red walls, before they were much less, since many of them were yellow.

This is one of the lines of the AAI: develop a portable technique, with non-destructive methods, that allows differentiating between the reds themselves and the originally yellow ones. They have already published a model with elementary tools. The next step is to develop the molecular model to know the temperature that each wall suffered. That's what they're doing now.

Source search

Another of the pigments they research is cinnabar. “It’s red, but very intense red, bright,” Maguregui adds. It was very expensive, “because it is not the land, but the mineral, and they did not have it there, they had to bring it.” Well, the objective of the research team is to know where they brought from. He says that in Spain there is a place where the cinnabar was extracted in Roman times. She can be the cradle of the Pompeii Cinnabar. However, there is also another mine in Italy, also from Roman times. Therefore, mineral collection is now underway in these areas for further analysis and observation of whether they can clarify the origin of Pompeii.

In addition, other analyses are being performed with the cinnabar, which degrades over time: red becomes black. For example, cite a wall of the Casa degli Amorini Dorati: “If you see and nobody tells you anything, you’ll think it’s black. We know it was red. Therefore, our intention is to clarify what were the causes of this color change. There are some hypotheses, but since it is not entirely clear, in the laboratory we will perform simulations to analyze the consequences that each agent has”.

Looking forward

In addition to clarifying what happened in the past, they work towards the future. For example, a biocide has been created with essential oils extracted from some plants of the deposit. These essential oils have been shown to kill fungi, but still only in the laboratory and with certain fungi.

Now they have to do more tests to confirm that in Pompeii it will also be effective and what its spectrum is, that is, who it affects. To do this, they will first create probetas, with materials like that of Pompeii, and then the final phase will come: to really try.

Mortar tests are also being conducted. According to Maguregui, cement or materials of this kind cannot be used on the walls of Pompeii, “not only for aesthetic reasons but because they cause damage to the original walls”. Therefore, they look for materials compatible with those used by the Romans. In addition, they should be easily removable if better materials have been invented in the future to replace them.

Thus, they use puzolanic materials. Volcanic minerals were used in Roman times to harden and reinforce. The intention of the AAI is that, analyzing the composition of mortars, they observe if they manage to make a similar mortar.

Machu Picchu

Apart from Pompeii, the IBeA group is also present in other sites. For example, Héctor Morillas Loroño investigates in the archaeological park of Machu Picchu. Among other things, it has analyzed its granite rocks and investigated the consequences of biocolonization.

In addition, in some shelters located on its inca route are pictograms and paintings that have investigated the pigments used in its elaboration. For example, carbon, hematite and beta-carotene have been detected in black, red and orange pigments respectively. Moreover, they have seen that the orange color was not the original; these marks are colonized by algae that give them the beta-carotene of algae. Thus, as in Pompeii, Chemistry is used to separate what seems, everything and everything.