The pigments in study

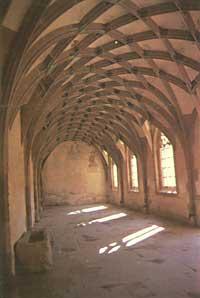

Visitors who visited the exhibition held last year in a city of Borgonia, along with traditional scrolls, tapestries and carvings, could find an explanation of the mysteries of molecular spectroscopy. The exhibition was organized at the Saint Germain Seminary in Auxerre. In the nineteenth century the monastic life developed in that same city was published. The aim was to make known the rich cultural stage between the years 840 and 908, that of the Carolingian splendor, since at that time the abatetxe was one of the most prestigious theological and philosophical schools. Spectra represent the interaction of light with materials and are generally a tool of inorganic chemicals. These spectra were part of the historical research that has existed after the exhibition.

To locate the enigma of manuscripts of alkmistic origin it is convenient to use chemical techniques. Many of these decorated documents have survived entirely and demonstrate the ability of medieval pigments to produce stable chemical compounds.

Initially, the alchemists unexpectedly discovered the pigment manufacturing pathways. As the Middle Ages progressed, the discoveries of Arab chemists spread to Europe and alchemy was gradually overcome. However, pigments only knew the empirical process. But with the same sense as the competent cook to handle the sauce, they used acetic acid to obtain lead acetate or limestone to neutralize acidity or ammonia to increase alkalinity.

They scrupulously kept the secrets of their business. Many recipes of medieval pigments were kept written or orally transmitted. However, when current chemists look for the chemical compounds of a fresco or manuscript, they should note that it has been intentionally left without mentioning the need for an essential step or component. However, recipes leave many questions unanswered.

At what temperature did iron oxide get into the oven? What did the animal that produced fermented manure eat in some chemical reactions? Today's chemicals will never be answered. But knowing the exact nature of the pigment, they can guess when a particular center or pigment was first used. Sometimes they can give new news about trade between peoples and the hierarchy of the social and economic situation.

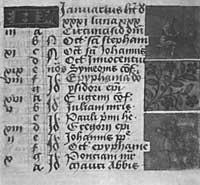

American Patricia Stirnermann is an expert in artistic history and a writer's specialist. He works at the Centre National pour la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in Paris. A year and a half ago Georges Duby, from the College of France, invited to participate in an interdisciplinary group that studied Auxer's abaty. The project began four years ago and has had the participation of about 30 researchers. Stirnermann's work consisted of analyzing a scribe embellished in Commentaries on Ezekiel, written by Haymon around 1,000. This manuscript is the only one that has survived from the two dozen believed to be written at that time.

Comments

Having references to the priest, it has been easy to know its origin. Author: Haymon; IX. Prestigious master of the twentieth century. His comments on the Bible were well known and copied many times. Ezekiel's book has an apocalyptic vision, so the nuns then carefully analyzed it. The millennium was about to end and they wanted to find out if there was any indication of the end of the world in the book.

Stirnemann has analyzed the style, content, calligraphy and beauties of the text, while Claude Coupry, a chemist, explored the manuscript sheets in search of the right places to take samples. It was about taking samples to analyze the pigments used in the beautiful ones. The National Library of France has sometimes allowed the extraction of samples of microns of lower slavery. Of course, no embellishment is proposed. The chemist looks for the mistakes of the scribe. The chemist has searched for stains, splashes or dirty drops made by the artist's brush.

Coupry, after finding the right spot, proved that it was the work of the original artist's brush. He then sharpened a wolfram coated needle into a sodium onitrate trioxide (V) solution until the end had the desired rigor.

The next step was the chemical analysis of the extracted sample. Coupry uses a Raman spectrometer. The spectrometer passes a laser beam along the sample and the lines of the spectrum of vibrations of the molecules are represented on a paper. This indicates how the laser beam photons in contact with the pigment lose or gain energy. As in any analysis technique, the obtained spectra should be compared with the standard component identification spectra. Fortunately, there are very large files of the Raman spectra, so the identification has often been immediate.

Comparing spectra, Coupry discovers that blue pigments are a mineral lapis lazuli. This pigment is obtained from the deep blue and XIII ultravarin gemstone. It is first cited in the 20th century. Coupry's analysis reveals that this pigment arrived in Europe at least two centuries earlier than expected. The origin of the pigment is Afghanistan.

Writing has brought to light more fascinating things. In a part of the offering image at the beginning of the writing, the priest Heldric is represented with his knees in front of the patron of Germain Auxer. This saint died in 448 and is buried in the crypt of Auxer. Their relics attracted many pilgrims. In the 20th century, a priest was miraculously cured when he was before his tomb. By analyzing the pigment, Coupry realized that some blue parts of the priest's dress were painted of unworthy (probably blue) and others of a precious lapis lazul.

This difference seems curious, but it highlights the nuances of medieval thought. In the Middle Ages, in the world of materials it was closely linked to ascetic value. Therefore, contracts for the realization of beautiful manuscripts often said the use of gold and lapislazul. The distrustful pattern would give the author an expensive ultralight (1 cm 3 approx.) sufficient to make a complete scribe to ensure that it would obtain a real good. It mentions the importance of the medieval hierarchy in the use of daracusa next to the interpretation of an indigenous and an ultralight in a small image by the authors of the writing.

GERO Coupry reviewed the red pigment from the main image of the same script. These images filled a whole page placed before baptism. At this point he found a stone on the road. It failed to make the right pigment spectrum. This inability proved very useful to Stirnemann. He was confirmed by concern for the bad appearance of the pages and the blasphemous character of the images. In a darker century after the liberal Caroline era, the two pages stuck. The spectrum destroyed the fluorescence generated by the remains of mariscadores.

Obstinate, Coupry took another path. He decided to study the red pigments on the walls of Abatetxe. Some frescoes of Abatetxe crypt of Auxer. dependents. The history of the restoration of the French churches is well known. Frescoes have thirteen layers of paint in some places. These layers witness the innovations that the fresco has suffered over the centuries.

Coupri studied these layers using chemistry tools. Using a surgical needle, take samples of a square millimeter. It is placed in the resin and checked with laser. Thus it got a spectrum of two red pigments. The first, formed by iron oxides, was used at the beginning of the Carolingian era. The other, in the Gothic period (XII. In the eighteenth century it was the bermelion used. Coupry continues to work to find the ingredients of the reddish ochre used in the decoration of the walls.

The study of medieval colors in France began in 1984, when the head of the National Library authorized the taking of microlagins from the skies. Initially the blue pigments used by the nuns of the Abatetxe of San Pedro del Corbie of Picardy were analyzed. St. Peter's Abbey was the second medieval Rome and the 8th. From the 20th century it had great wealth and power. His scribes and nuns fought with ultramarine, azurite, indigo and artificial copper blues. The massive use of lapis lazuli in Corbie, XII. The researchers of the 20th century trade routes forced to change prejudice.

It is evident that the study of pigments allows to know the cultural and technical exchanges throughout Europe. That is why it is intended to repeat studies such as that carried out in Auxer and analyze, for example, the cultural substitutions that occurred as a result of the conquests of the Normans.

However, researchers expect new technological advances such as the spectrometer that will replace the laser with the infrared. It is intended to use non-destructive techniques to be able to perform several analyses on the same sample. For example, techniques used now only support inorganic samples and researchers may know that indigo has been used. Not so the plant from which it is extracted, since organic analysis destroys the sample.

The infrared laser will allow a complete analysis of the matter without damaging it. The first infrared lasers are now being published and because constant innovations are appearing, they will also be able to analyze organic matter.

On the other hand, knowing what the pigments are and where they were obtained can help a lot to restore the ash, tapestries and apeos. In fact, at this time you can get very interesting information to launch new techniques that allow to slow down or return the chemical processes that damage these works of art. If there are many sick manuscripts and their window of hope can only be extended by chemistry.