Baron Nopcsa and dinosaurs of Transsilvania

Transsilvania reminds most people of the territory in which the bloody Count Dracula lived. However, few know that we have one of the most important paleontological heritage of our continent, since it is very rich in dinosaur remains. Thus, the paleontological findings made in the shade of the Karpato mountains have provided us with a large amount of information on the latest dinosaur fauna species in Europe, which lived 70 million years ago.

In Transsilvania, as mentioned earlier, the history of the discoveries of dinosaur remains is closely related to the life of a peculiar paleontologist, Baron Ferenc Nopcsa. Just over a century ago, that is, in 1895, Ilona Nopcsa, daughter of Hungarian nobles, discovered dinosaur fossils in family lands near the city of Sinpetru, in the heart of Transsilvania. This led Ferenc to his 18-year-old brother in search of paleontology and fossils. The young Ferenc Nopcsa took little time to find fossils of high scientific value in the outcrops of the H</a> river, including a full-headed hadrosauru.

Ferenc was studying in Vienna and in one of his travels he taught fossils to his prestigious professor and geologist Eduard Suess. Suess soon realized its importance. The bones come from the sediments of the Upper Cretaceous and, being the last European dinosaurs, opened the doors to investigate a topic little worked until then. The Vienna Academy of Sciences planned paleontological excavations in the “Guide” basin, but these economic problems were not carried out.

Suess, in view of the student's good doing, proposed to Nopcsa herself research. Although Nopcsa had no paleontological training, he accepted the proposal and the Transsilvania dinosaur began to investigate as self-taught. Thus, in June 1899, he presented to the Vienna Academy of Sciences his first work, the research of the dinosaur skull “ahate-moko”. This opened the career of the prestigious paleontologist.

Nopcsa's paleontological work focused on the research of Transsilvania's fossil vertebrates, especially dinosaurs. In the Nopcsak Basin he organized numerous surveys and excavations. In this way, he collected the rich collection that currently exists in the Natural History Museum of London. He spent over thirty years researching the geology and paleontology of Transsilvania and wrote about twenty scientific articles on these subjects. He was the first to describe the varied fauna of reptiles, dinosaurs, turtles, crocodiles and pterosaurs, among others.

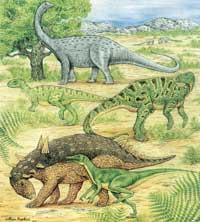

Despite finding many fossils, dinosaurs are the most abundant fauna of Hategi. Nopcsa identified five different species of dinosaurs: four herbivores (Telmatosaurus and Rhabdodon ornithopods, Struthiosaurus ankylosaurus and Sauropod titanosaurus) and one carnivore. The most important feature of these dinosaurs is their small size. For example, those of Telmatosaurus and Rhabdodon were between 4 and 6 meters long and those of Struthiosaurus were less than 3 meters long. Nopcsa deduced that the dinosaurs of Transsilvania were dwarfs and believed that this nanism was related to the European island geography of the Upper Cretaceous.

At that time, the continent we know today was only a group of islands surrounded by shallow sea. Nopcsa thought that the main factor of dinosaur nanism was the small surface of the earth and its distribution in islands. Therefore, mammals (elephants, rhinos, cervids, etc.) that inhabited the islands of the Pleistocene Mediterranean. compared to Nanism. According to Nopcsa, this isolation explains why some components of the fauna maintain their primitive characteristics.

In the article published after his death, Nopcsa proposed that the reptile fauna of Transsilvania was mixed. This mixture of fauna was formed by a primitive European fauna evolved by its part and by a specialized fauna coming from the continent of the southern hemisphere. This paleobiogeographic model did not correspond to the fijist ideas of the time and therefore did not receive approval from scientists. Nopcsa was a fervent defender of the “plate tectonics” theory proposed by Alfred Wegener.

The movement-ideas were accepted by few and, for example, paleontologists considered that migrations could only be carried out using intercontinental bridges. Nopcsa was excluded from these ideas and is therefore a pioneer in the research of the affinities of Mesozoic reptiles.

After the death of Nopcsa, the vertebrate fauna of Transsilvania was hidden for almost half a century, from 1933. In the late 1970s, Romanian and foreign paleontologists and geologists resumed the excavations of the Huhezi Basin. In the excavations since then, in addition to the reptile fauna described by Nopcsa, many new fossils have been found. Among them, remains of bone fish, amphibians, lizards, carnivorous dinosaurs, hadrosaurs eggs and multituberculated mammals.

The vertebrate fauna of Transsilvania competes with the diversity of deposits for the Treviño Consortium, Catalonia, Langedo and Tests of the Cretaceous Superior. His main interest lies in knowing what were the continental ecosystems formed by dinosaurs and other beings destroyed in the final biological crisis of the Mesozoic Era.

The cause of the destruction of dinosaurs is still not entirely clear to scientists, but these reptiles from Transsilvania have helped us see that they could suffer the drastic climate changes that occurred in the Upper Cretaceous. On the other hand, since at this time the populations of European fauna are still very diversified, it can be thought that there was no decline in dinosaur species. Affirming this, it would reinforce the hypothesis that the destruction of dinosaurs was violent and not gradual.

In short, a century after its first discovery, the vertebrate fauna of Transsilvania has not yet revealed all its secrets. May all the wisdom gathered for a hundred years be a tribute to the man and the scientist who left his shadow in the fauna of the European Higher Cretaceous.

Barón NopcsaF erenc Nopcsa Von Felsö-Szilvás, later known as the Baron Nopcsa, was born in Sazel de Transsilvania (in Hungarian Szacsal) on May 3, 1877. Ferenc was master of the Seles of Emperor Franz Joseph and Empress Elisabeth Empress. Nopcsa was the nephew of the Baron (then Transsilvania was in the Austro-Hungarian Empire). Nopcsa demonstrated from a very young age his fondness for natural science and in 1903 he graduated from the University of Vienna. His good economic situation allowed him to devote himself fully to science by visiting research centers and museums all over Europe. The passion for adventure led him on several occasions to Albania, where he called this terrible homeland geological and ethnographic works. During World War I he worked as a secret agent of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He also tried to achieve the reign of Albania, but without success. Later, in December 1918, Romania conquered Transsilvania and Nopcsa lost most of its assets. In a conflict with the Romanian peasants his head broke and since then he suffered from periodic nervous system disorders. The weak creation that Nopcsa had overlapped with a hard and proud character. The image of some sectors about Nopcsa is composed of picturesque characters, simple diletantes, heterodox lifestyles, adventurers and homosexual tendencies. He was a first-rate scientist and XX. In vertebrate paleontology of the first half of the twentieth century it is very remarkable. The intrinsic curiosity, the great scientific culture and the knowledge of the scientific literature of the time, affected various subjects of the natural sciences. His scientific contribution in several languages (Hungarian, German, English, French and Albanian) extended to areas such as reptile paleobiology or to broad topics such as paleobiogeography, structural geology or evolutionary biology. Nopcsa's scientific work was awarded important positions. Between 1925 and 1929 he was director of the Royal Geological Institute of Hungary, member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and Correspondent Member of the Geological Society of London. Due to serious health and money problems, in April 1933, he decided to end his life and committed suicide. Nopcsa was the last representative of one of the oldest noble families in Transsilvania and one of the largest bastions of Hungarian science of this century. |