Natural adhesives natural adhesives

Undoubtedly, the world of adhesives is an ancestral issue. The Romans, for example, used the brea extracted from the wood of the pines and the wax of the bees, among other things, to build ships -- the wax of the bees is still used as adhesive. The Aztecs, for their part, mixed the blood of some animals with clay and used it to join the stones of the buildings, and many of those buildings are still standing.

These adhesives of animal origin are more powerful than many of the current adhesives and are used in the restoration of wood and carpentry, among others. Once golden in the water and heated in the bath Maria, they are used hot and acquire form of gel when cooling.

They are characterized by their degree of adhesion and elasticity. In all cases, they require a minimum concentration to avoid stresses or tractions in adhered materials. The adhesives based on bone collagen, blood albumin and milk casein protein are probably the most commonly used adhesives of animal origin.

Among the vegetable adhesives, the most common are starch and dextrins from corn, wheat, potato and rice. They are used to glue paper, wood and textiles. These starch based adhesives have been used for thousands of years. Starch is not actually an adhesive, but by boiling in the water its granules swell and become viscous. This is what gives you the ability to paste. On the other hand, Arab gum, agar and algine, among others, could be used to paste the envelope seals when they are wet. Cellulose adhesives are used to paste skins, fabrics and paper.

XX. In the eighteenth century, the development of synthetic adhesives based on several polymers derived from oil began, replacing natural adhesives with synthetic adhesives in many applications. At present, they have higher yields and application fields than natural adhesives.

The first synthetic adhesive was surprised by several chemicals from the Eastman-Kodak company. The accident and, at the same time, the discovery is due to cyanoacrylate. It was discovered by researchers Coover and Fred Joyner. While investigating in the laboratory a heat-resistant polymer, Joyner established a cyanoacrylate layer between two prisms that, just to realize, were stuck together. It was then that the history of cyanoacrylates or adhesives known as Superglue began. Cyanoacrylates are monomers or raw materials of the adhesion polymer. These monomers are quickly polymerized against basic substances. He thinks they also polymerize quickly with water (water is a weak base).

Therefore, whenever we open the tube of Superglue, it is enough that the ambient humidity is multiplied by the monomer and paste two surfaces. Perhaps you will now understand why it is polymerized so quickly in our hands or fingers, right? The water we have in our hands or fingers is sufficient to initiate the reaction of polymerization and solidify the liquid from the tube.

One of the most powerful natural adhesives

According to a study, a bacterium that lives in the pipelines of rivers, streams, or water streams produces and uses one of the most potent adhesives of nature so that it can be in place.

The study, conducted by researchers from the universities of Indiana and Brown of the US, has found that the release of the bacterium Caulobacter crescentus through a glass pipette requires a force of micronewton. Extrapolating this data can be said to be a force equivalent to a weight of 4 tons on a euro coin, which is approximately 70 newtons per square millimeter. The most powerful adhesives we use in today's society stick with a force of about 30 newtons per square millimeters, which means less than half the strength of this natural adhesive.

The bacterium Caulobacter crescentus adheres to the stones and the inside of the tubes through a long and thin leg, under which are formed some molecules of sugar as adhesive. Therefore, the next challenge of the researchers is to produce this type of sugar in large quantities, but with the characteristic that the adhesive does not stick in the handling tools, since otherwise it could not be used.

This bacterium is not the only one that produces its own tail. Two or three years ago, researchers at the Max Planck Institute saw that the tarantulas give off an adhesive silk on the feet. The discovery was by chance: While investigating the locomotion of the zebra tarantula of Costa Rica ( Aphonopelma seemanni ), during a break he forgot to turn off the camera, because when they returned to work they realized that the tarantula had left some traces and seeing the camera saw that the taranttica had shed the silk of the feet.

Apparently, the taranttica uses the silk removed from the feet as adhesive to avoid, among other things, the slip when climbing through the wall.

Imitating nature

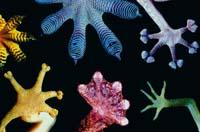

Something similar happens with ours. The keys are known for their ability to stick, for example, they can hang from the ceiling from a single foot without falling. Recently, researchers at the University of Manchester obtained a new adhesive material, after revealing the secret of the keys and knowing what this capacity was due to. It seems that the ability to stick the keys to any place is due to the millions of hairs they have on their feet.

The material obtained by the researchers also has this characteristic, that is, once the tape is removed there is no trace. It is also more adhesive than any other adhesive. The drawback of this material is that it is still very expensive to be produced at industrial level.

In addition to fats, mussels also have some proteins with adhesive properties. In fact, mussels produce a more powerful resin than any current commercial adhesive: 3,4-L-dihydroxyphenylalanine (DOPA).

Recently, researchers from the Northwestern University of the United States have produced a new adhesive that combines the adhesive properties of both animals. In this revolutionary material, the strands that have hooks on the feet have combined the ability to move through vertical flat walls and the ability to stick mussels on wet surfaces.

For the development of the adhesive, a coated layer of silicone nanollos was prepared to form a layer similar to that of the people's films. This material could be glued and dropped on the walls, such as keys. However, it was detected that the humidity prevented this submarine. To combat it, the researchers covered the ends of nangallins with a synthetic polymer of the same characteristics as the amino acid DOPA produced by mussels, and saw that the new product was able to adhere also to the wet surfaces.

All these natural adhesives have been the subject of numerous studies, many of which have contributed to the development of synthetic adhesives. The goal is always the same: to connect those who are separated.