Migration as a fishing guide

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“There is no bishop who has not been a priest.” We will not focus on the ecclesiastical theme, but on the influence of experience or marine life on the behavior of our suburbs.

In this sense, fisheries science, including fish migration, has taken advantage of what has been learned for years by seafarers and experiences lived from generation to generation. Fishermen have always followed in open sea the species that interested them and, incidentally, and sometimes without realizing it, they have perfectly drawn the migratory routes of these species. Turning popular knowledge about migrations into scientific hypotheses and confirming this hypothesis has been the real challenge of marine sciences. Our story will aim at the last link of this chain that is often easily broken: to socialize this scientific work.

What is migration?

Before materializing the skeleton of this story, let us try to situate the subject. What is migration? In the encyclopedic dictionary Harluxet the term migration is defined as: “Some types of fish, birds, insects and other animals in the environment (seasons, climate, variety of food, etc.) in search of a more suitable one, the change of habitat they make and that implies an intermittent displacement between both habitats”.

This very broad definition includes most of the types of fish migration listed below and will be useful to us. To carry out the habitat change that is defined, sometimes displacements are very long, sometimes short, while habitat change occurs through the oceans, sometimes from sea to rivers and vice versa. Among the reasons that hide under a more favorable environment, sometimes the criterion of food option prevails, while other times the search for more suitable places for reproduction or environmentally richer places of life prevails. Sometimes... and so to form a long and endless list. Let us go step by step to answer the following questions in our brief narrative.

Why and for what do migrations do?

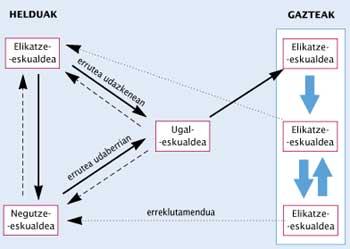

When it comes to explaining the reason for migrations, we must disembark many different reasons, although the most common one is known as reproductive migration. During reproductive migration, the animal travels from the feeding area to the breeding areas. Its aim is reproduction and moves from an appropriate area for the survival of the adult animal to a more suitable area for eggs and larvae. So, after reproduction and guided by the stomach, take the migratory route back (Figure 1).

However, other migrations are not related to reproduction and are carried out with the intention of finding useful food sources or more suitable living conditions at all times.

On the other hand, considering the change of habitat that occurs when carrying out these migrations, we can launch a new classification of the types of migration. Thus, if migration is between seas and rivers we say it is a diadromic migration. However, when the transfer takes place in the same area, migration is carried out by zones: oceanodrómica migration (displacement occurs in the ocean or in the sea) and potadromic displacement (movement occurs through the river).

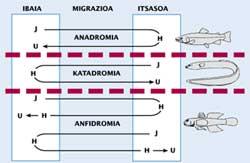

Special mention deserves diadromic migration. The animals that carry out this migration, at certain times, are directed towards fresh water or the other way around, usually for reproductive purposes. Diadromías can be of three types: anadromía, catadromía and anfidromia (Figure 2).

The anadromic species are born in freshwater, the juveniles migrate to the sea to reside in it, and then reproduce again in freshwater; among this type of migratory species, lamprea, salmon, sturgeon, etc. we have them. On the other hand, the catadromic species, after being born in the sea, go to the rivers to spend most of their life in this environment, even if they return to the sea to the setting; the best known examples of these migrations are the eels and the angles. Finally, the amphibian species performs several migrations from one place to another during its lifetime, and reproduction occurs in one place or another.

For the moment, we have only clarified two answers to the questions raised above. Let's keep looking for more answers.

Migration mechanisms

The movements of the fish have fascinated human beings over the centuries, even more so when it is seen that in the same seasons they traveled thousands of kilometers to return to the same places. Thus, the question that has lasted for years comes to mind: how do they guide the way and what mechanisms have they developed to seek their destiny?

Scientists have explained several explanations about the orientation of fish: geomagnetic and geoelectric fields, currents, smell, temperature changes, salinity changes, sunlight and polarized, etc. The explanation of all these reasons and the description of all the mechanisms will cost us a lot, not the object of this article, but some simple examples will allow us to better understand these mechanisms.

Solar orientation: nowadays it is quite clear that fish, like birds, use the sun to orient themselves. If the fish find good light and sky conditions, they detect the changes that occur in the daily solar cycle and use this information to orient themselves in the water. To do this, the fish must be aware of the changes that occur in the altitu (angle formed by the solar rays compared to the vertical plane) and in the azimut (angle formed by the solar rays compared to the horizontal plane). However, both in cloudy days when there is no sun, and at night, other mechanisms interlace to orient themselves in the water.

The fact that fish own a magnetic compass means being able to perceive and orient the earth's magnetic field. The fish with this sensitivity are abundant, such as those of the subclass elasmobrankio, those of the angiliforme order, the salmon of the genus psalm and the tuna.

Water currents, in addition to serving for the transport of eggs, larvae and adult fish, can cause guidance signals that can detect fish. Once the water stream is found, the fish can orient in current and swim in their favor or against.

The smell that fish use to orient themselves in their path was the first proposed mechanism to answer the question of how they oriented themselves. It occurs mainly in species that perform anadromic migration. Fish learn the characteristic smell of the river that has been their place of birth at an early stage of their life and, subsequently, the discovery of this smell is what guides the evolution of reproductive migration. That learned smell pushes the fish to the river that has been born, without just emptiness, to reproduce.

Temperature seems to be the most important environmental factor that triggers fish migration. In addition, both directly and indirectly, it has a great influence on the mechanisms of orientation of the fish. The movement of many migratory species is conditioned by temperature change and they follow their travels with their favorite isotherms.

This response to temperature can be direct, at a certain or indirect temperature, associated with the abundance of food. Plankton blooms are related to temperature changes, so fish look for the right temperature to find food.

Migration research

As mentioned in the introduction, the fisherman, and man in general, has known for centuries the existence of fish migrations and, in addition, the availability of a rich source of food in the same season of the year without fail, has become a common phenomenon. In many cases, coastal communities also rely on these migrations to ensure their survival. So how do you research migrations?

The most widespread, useful and yet most useful method of migration research in the last century has been and remains the marking of fish. Through these fish identification marks you get very useful information to draw the migration routes of the fish. In the following lines we will try to assimilate this method in a simple and understandable way: once the fish has been caught alive and received information about it (date of marking, position, weight, length, status, etc. ). ), is marked and left in its natural environment, water.

The mark placed on the copy (Figure 3) contains a code and the name and address of the person or entity that marks it (to know who should be returned). Thus, once the fish has been recapitated, together with the collection of the brand, the same data are measured again. Consequently, although the complete trajectory of this fish is not known, it also serves to know the displacement it has made and its growth in that time.

The simplicity of this method is evident and does not present great difficulties in carrying it out. However, there are three drawbacks that we can find in the mentioned method: the loss of marks, the damage that causes the fish and the low probability of recovering the mark (either because the fish has not recapitated or because the brand has not reached the hands of researchers).

Despite being such a simple and simple method, in recent decades there has been a great advance in this field of research. That's why there's a lot of diversity and variety around brands, like writing another article, but we'll only offer you a supervision. In general, there are two types of brands:

- Outer mark: inserted into the skin of the fish and visible to the observer.

- Internal marking: inserted inside the fish. Not being spectacular for the observer, we can detect it in two ways: by implementing a special external brand or by sensors with different industries after fishing fish.

Both internal and external marks may be of different nature (Figure 4):

- Conventional: support with a code and an address.

- Pop-up mark: collects the fish position, depth and temperature of the water every hour. The information obtained is received via satellite, when the mark emerges on a pre-programmed determined date (Figure 5).

- Internal and archive: like pop-ups, but it is an internal brand. This receives the temperature of the animal and the water (it has an extension to the outside).

However, there are other ways to investigate migrations. On the one hand, the catches of the different fleets transmit a lot of information, such as observing the catches of each season of the year, we have realized the evolution of the different species. At different times of the year, the same species of fish is not caught in the same place and this fact, at least qualitatively, allows to draw migratory routes. On the other hand, the parasites of an animal can also offer useful information. This technique is applied when the fish is contaminated by a localized parasite. Thus, once the migration has occurred, if the parasite fish is caught in an area where the parasite does not live, we can know where the displacement that the fish has made has begun and where it has ended.

And all this affects fishing?

The quick reader, after looking at the title, would have already realized that the answer is yes. As already mentioned, over the centuries, several coastal communities are subjected to fish migration waiting for the support of a certain station. We know the fisheries that take advantage of migration around the world, and although it is not possible to mention all of them in this article, we will try to summarize close examples.

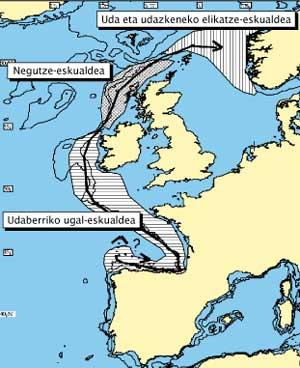

The verdel, after spending the summer season until winter in northern Europe, in early March, paying attention to reproductive migration, enters the coast of Hondarribia by the east of the Gulf of Bizkaia. As the spawning season progresses, it heads west along the Cantabrian Sea, before starting again in summer the long road north (Figure 6).

Although it is not very clear where winter passes, no one knows where spring passes. The queen of the lowland fleet appears when the water of the Bay of Biscay has a suitable temperature for anchovy, to start its breeding season.

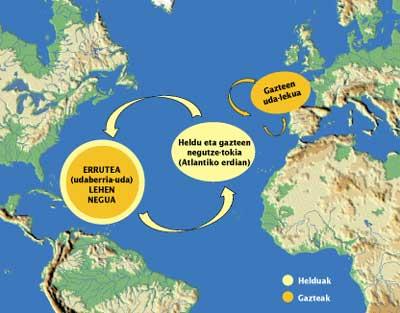

The beautiful and the cimarron that exploits the Basque fleet of lowland are species that carry out long migrations. The Atlantic travels through different periods and phases of life seeking the most suitable conditions to live and reproduce. Thus, adult specimens, after their placement in the reproductive area of the Caribbean Sea from April to September, migrate to the wintering areas (Middle Atlantic) to spend the winter (Figure 7). On the other hand, the juveniles of bonito spend the first four winters of their life with the adults in the wintering area.

At the arrival of the reproductive time, they still have no reproductive capacity and are headed during the summer to the Gulf of Bizkaia to feed. However, the bluefin tuna (figure 8), after being born in the Mediterranean setting area and spending its first year on the Moroccan coast, during the summer migrates to the Gulf of Bizkaia to fill the gut. Towards winter it returns to the Moroccan coast. Once it reaches maturity, it returns to the Mediterranean Sea and passes all year round, although some specimens travel in summer to Norway.

In spawning season, in search of the right conditions, a south-north migration is believed to occur. Thus, when the set time begins, between December and February, both the capture and the largest amount of hake occurs in the southern area of the Bay of Biscay. As the set time progresses it migrates north and during the months of June and July is in the Irish Sea.

Although there are not too many examples of this migration some time ago, our grandparents remember that they once saw salmon jumping on the river (Bidasoa, Urumea, etc. ). Adult salmon roam the river between December and January.

Despite this, the Basque fleet tries to make the most of seasonal migratory species. “Seasonal” advises us a Basque cook known to all. If we combine this game of words with our gastronomic culture, it is easy to warn which species visit our coast following their migratory routes. The elder ele, zuhur ele, leads fishing migration.

Orientation, navigation and piloting

Fish, and in general many animal groups, have the capacity to move, orient, pilot and navigate, and use these three mechanisms to reach their destination in migration from one point.

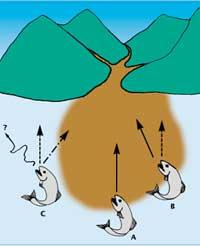

Imagine that a fish is at the point of origin of its migration and that its destination is the mouth of a river. This fish, by means of an orientation mechanism (solar rays, magnetic field, etc. ), takes a direction and heads towards its destination. Fish is found in case A. Guiding. Suppose now that the current or other factors cause the same fish to move along the way (case B); it is clear that keeping the previous orientation (arrow with script) will be lost. Therefore, with the help of a stimulus you have received, navigate to reach the destination.

Navigation is a guideline correction (continuous arrow). In case C, however, the animal has moved and lost the stimulus to carry out the correction (wrong arrow). Then, lost, it begins to be piloted (it can make a map with the help of marks or stimuli of the environment) in search of the stimulus it needs. Once this stimulus is located, it will begin to navigate and orient towards the destination.

Therefore, it is not possible to orient itself if the fish is not able to navigate or pilot. Each mechanism is related to the other and the ability to carry out the three actions will allow the fish to reach its destination.

Bond, C. R.

Biology of Fishes.

Philadelphia:

Saunders College

Publishing. 1979.

Jules, J.L.

Cimarron.

Basque

Government Central

Publications Service.

1994

Encyclopedic Dictionary

Harluxet.

Helfman, G.S;

Collete, B.B.

and Facey, D.E.

Diversity of

Fishes. Blacwell

Science. 1997.

McKeown, B.

Fish migration.

London: Croom

Helm. 1984.

Uriarte, A and

P. Lucio.

Migration of adult

mackerel along

the Atlantic.

European shelf

edge from a

tagging

experimental in the

south of the Bay

of Biscay in 1994.

Fisheries Research

50:129-139. 2001.