Leonhard Euler, 300 years

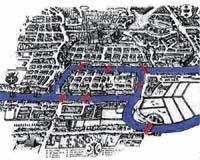

Eule's life is divided into four times and three places. Born in Basel (Switzerland) in 1707, the eldest son of a Protestant pastor, he grew up in the neighboring village of Rilehenengo. Basel is the oldest university in Switzerland, XV. Born in the 20th century, the brothers Jakob and Johann Bernoulli of Basel were one of the greatest mathematicians of the time. Upon entering Euler, professor at Johann University, very young, at the age of 13. Thanks to him, Euler took the path of science leaving aside the religious studies that his father proposed. In 1726 he completed university studies and the following year he received the offer from Russia: Proposal to work at the Academy of Sciences recently created in St. Petersburg by Tsar Peter Handia. There was Daniel Bernoulli, son of Johann and close friend of Eule.

He left Switzerland not to return. At first he found a confused atmosphere in Russia, when the tsarist Peter and the zarina Catherine had already died, and until 1730 he had not really dedicated himself to the Academy. From then on he became increasingly responsible and the success of the work of the coming years gave fame to Euler. When the political environment was remixed, he moved to the Berlin Academy of Sciences.

Founded on the initiative of Leibniz, the Berlin Academy was about to disappear until Frederick II tried to restore it. The king wanted to bring him at all costs to the Euler Academy and get it in 1741. Eulertuz had very fruitful years in Berlin, but when his relationship with the king deteriorated, he ended his 25-year stay and returned to St. Petersburg.

It was like returning home, as in Berlin it maintained a close link with the Russian Academy; for example, almost half of the articles written in Berlin were published in the Saint Petersburg magazine. The year after his arrival he lost one eye and was blind. Therefore he did not abandon scientific work and, although he could not write on his own, he had collaborators to copy what he had said. Perhaps that is why, and even if it seems surprising, in this last stage of life it produces works faster. While still working, he died in 1783 in St. Petersburg.

Euler and academies

After the student's time, Euler was never in a university. But that is why he was able to do everything he did. Still universities were not real research centers, and the work of knowledge generation was assumed by academies and scientific societies. First XVII. They were born in the nineteenth century and proliferated during the time of the Enlightenment (also in Euskal Herria was created the Real Sociedad Bascongada de Amigos del País).

All these entities were not equal, neither in importance, nor in objectives, nor in financing. Some, in the style of the two Academies, received Euler, with the support and money of the kings. It was an honor for the Academy -- and its sponsor -- to have the presence of prestigious scientists. To achieve this, he offered them a good salary and good living conditions and, in most cases, the freedom to work they wanted. There were also rivals in the courts, for understanding that maintaining the Academy was spending money on useless actions. From time to time, however, academics worked on hands-on work. In Eule's work, in addition to mathematics or mechanics, we find artillery, navigation, widow pensions and others.

XIX. In the 20th century, after the French Revolution, there were important changes in the teaching system. From there, scientists and researchers worked mostly in universities and the role of surviving scientific societies changed. Belonging to the academies was an honor, but the salary was perceived elsewhere. Among the academies that maintained great strength and influence is the Russian Academy of Sciences (former Soviet Union), heir to that of St. Petersburg, meeting point for leading scientists. The success of Russian mathematicians, not always known, is probably on the basis established by Euler.

Eule Contributions

XVIII. The classification of 20th century science was not the current one. The Paris Academy, for example, had under the name of mathematics geometry, astronomy and mechanics, and in the section of physics anatomy and natural sciences. Evidently, what we call physics today was accompanied by mathematics. Euler was a complete mathematician, in the sense of his time, since together with purely mathematical works we find mechanics, hydrodynamics, astronomy, optics, etc.

Recognizing Eule's contributions, his name appears in several concepts and objects: Eule formula (in complex analysis), Eule numbers and polynomials, Eule characterization, Eule constant, wind coordinates, wind graphs, Eule and Euler-Lagrange equations, Eule angles, Euler-Maclaurin formula and others.

When Euler died, the infinitesimal calculus of Newton and Leibniz was one hundred years old and a degree of spectacular development. So great that along with traditional geometry and episodes called algebra another was created: mathematical analysis. He also became the most important and his main responsible was Euler. XIX. In the 19th century, Frenchman Arago said about Euler: "We could call it embodied analysis with little metaphors and really no hyperbolos."

The development of analysis revolutionized the offer of mathematics. It was a powerful tool for the study of physical phenomena. By expressing them through differential equations and solving the equation, a description or evolution of the phenomenon could be given. In all sections of this program we find Euler, both inventing concepts and methods of calculation and applying. But even more: for many years the exemplary books he wrote were used as textbooks to work the calculation without being a teacher.

Eule's work was so wide and varied that it is impossible to summarize it in a few lines. Let us say, for example, that we also owe him the theory of numbers or the genesis of higher arithmetic. After researching Pierre de Ferma's untested comments and results from the last century, Euler nuanced, extended and structured them, giving them their own space within mathematics.

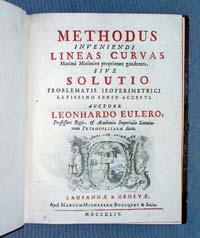

The writer Euler

"Read to Euler, who is the master of all of us," Laplace said. This phrase shows that Euler was a master of mathematicians who came to his side. And Euler gave them what he had read, because he became the most prosperous author of mathematics to leave all his scientific legacy.

During his life he published 530 works, with more than twenty great books. Upon his death, 240 other articles remained pending at the St. Petersburg Academy, the latter appearing in 1826. And more, because in 1844 unknown texts were found in his house. A hundred years ago a complete catalogue was made and a list of 866 works was drawn, without letters. Its languages are Latin, French, Russian and German.

It was the XIX. The intention to publish all of Eule's works in the 19th century did not prosper. A hundred years ago, in 1907, on the occasion of the bicentenary of the birth of Eule, the Swiss Academy of Sciences created a special commission, the Euler commission, in order to publish the collection of all his works. Among many incidents, one hundred years later work is about to end. Eule's works and expert comments will complete 72 volumes. Only the last two are missing and it seems they will be ready for next year.