Cave art in the age of digitalization and AI

The revolution of digitization and artificial intelligence has reached all walks of life, including the caves' cavities, and has researched, among other things, cave art. With the help of new technologies, contemporary archaeologists have not only discovered hidden treasures, but have also created an objective and universal method to study and understand them better.

Archaeology has always been an example of interdisciplinarity. José Miguel de Barandiaran Aierbe and his environment also gathered in their archaeological research methods and approaches from different fields of knowledge, such as speleology, geology, paleontology, anthropology, ethnography, chemistry... Over time, archaeology experts participate even more in archaeological research, in order to get the most complete puzzle with the remains of the past.

The last example of this evolution is the work done by archaeologists of the Institute of Prehistory Research IIPC of the University of Cantabria, Iñaki Intxaurbe Alberdi and Diego Garate Maidagan. In his opinion, digitalisation has represented a revolution in the research of cave art, from the discovery of images before becoming invisible, to its conservation and to the obtaining of new conclusions.

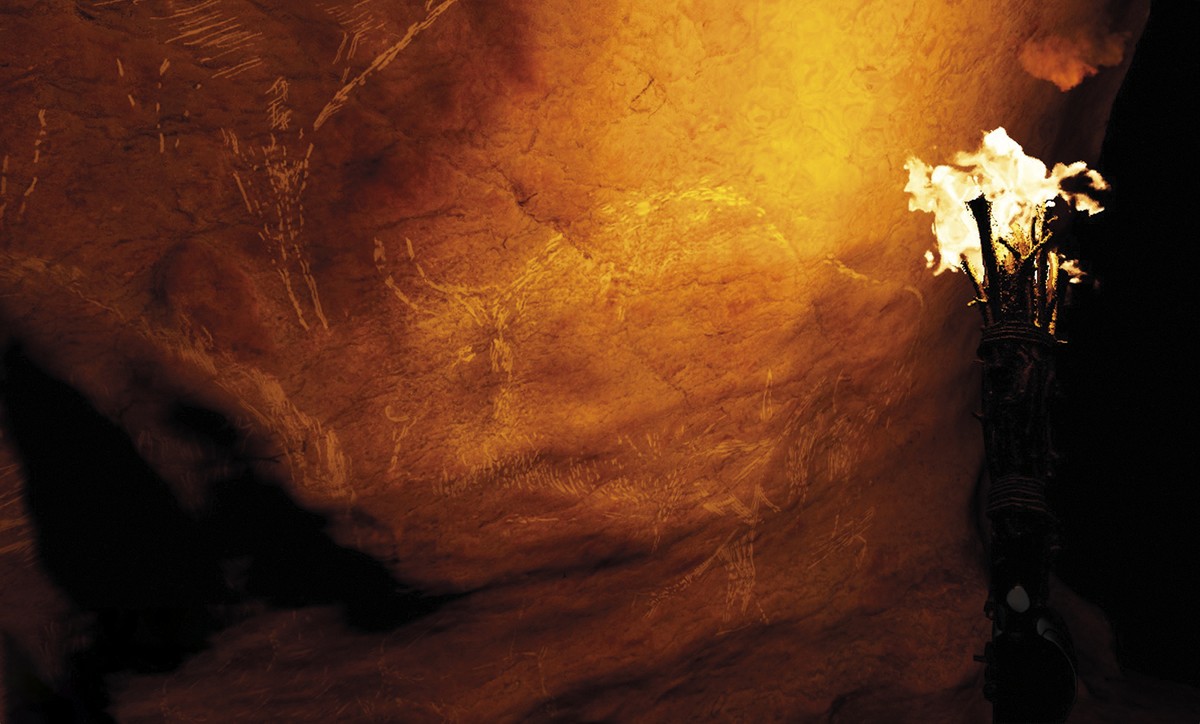

As a sign of this, new images have been discovered in the caves that were already known beforehand. Intxaurbe explained that the DStretch software application has been used for this purpose: “This application alters the natural color and distinguishes the colors that are not seen otherwise. This helps us to see images that are not perceived with the naked eye and interpret them; for example, where you suspect something, you can identify a bison.”

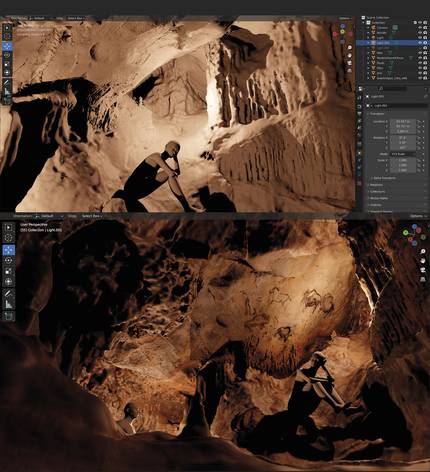

He then gave another example: the replicas. “Today, thanks to digitalization, we are able to do things that were impossible 15 years ago. Now we can bring the cave itself to our computers, and so we work from the laboratory, the university or from home, as they do in other areas, like urbanism or urbanism.”

“This is very important,” Garate stressed. “In fact, in some caves, the entrance is very restricted or difficult. For example, in the cave of Chauvet (Ardèche, France) it is not appropriate to introduce anyone for conservation reasons, but only the researchers of the project enter and within certain time limits. On other occasions, the entry has been closed by geological movements or is very difficult. The cave of Cosquer, for example, is located in Marseille (France) and is under the Mediterranean Sea. Thus, digital replication is not only for dissemination or museums, but also for research.”

Objectivity as an objective

For Intxaurbe, another of the great novelties of digitalization has come from the hand of interpretations or inferences. “Starting in the middle of the last century, statistics began to be used in archaeology and in recent times has gained a great deal of weight.” In particular, Intxaurbe has demonstrated in his thesis that the function of the Paleolithic cave art can be divided into four blocks using 3D technology, geographic information systems and multivariate statistics.

As explained, in the 1990s statistics were also used to make such classifications, although some criteria were not objective, such as, for example, the degree of accessibility of a place. “For example, a biologist and archaeologist may have a different view of accessibility. Now, through technology, the program analyzes the cave image and gives a numerical value to accessibility. For statistical analysis we use this number and the result we obtain is objective and universal. It doesn’t matter if someone does it in my place, if the cave is from here or from Andalusia,” Intxaurbe said.

In particular, he analyzed nine caves of Euskal Herria, one from the north and the other from the south, all from the time of Madeleine, that is, from the last time of the Paleolithic cave art (from 18,000 years to approximately 13,500 years). And it's come to classify the images into four groups: those that have a xamatic function, those that have the rites of moving to maturity, the sculptures and clay prints in hidden places, and the abstract signs.

Garate has recalled that in archaeology, from its beginnings, the interpretation has been very subjective. “Quantification is therefore essential for objective conclusions. In addition, today, open science is the key, that we all share the same information. And that's what we can do today in rock art as well. However, there are limits. For example, the files and data we use cannot be uploaded to the Internet, as they have a lot of terabytes. That’s the goal, but at the moment we’re at the center of the road.”

As he pointed out, as in the other areas, the objective is to follow the FAIR criteria in archaeological research: data must be easy to locate, ensure access to them, be accessible to other data and tools and, finally, reusable.

Open science and artificial intelligence

Intxaurbe has made the thesis with these criteria, under the direction of Garate and Martín Arriolabengoa Zubizarreta. And it recognizes, though surprising, that its classification partly coincides with the proposal of the structuralist archaeologist André Leroi-Gouhan in the middle of the last century.

“Leroi-Gouhan realized that there were images to see and others to hide them. But, of course, the methodologies he used to deduct it did not meet the FAIR criteria. Thus, when the tables were published, no one was able to reproduce them because it did not reveal the path he had followed to reach the conclusions. They were based on the principle of authority for the dissemination of their results. However, today there is no longer a class; anyone can receive information and, if the research is correct, they will reach the same result.”

As with the principle of authority, technology is useful for overcoming other emissions. In this sense, Intxaurbe and Garate have recalled the work of Verónica Fernández Navarro, a teammate of the Euskaltel Euskadi. In fact, it was not questioned before that the authors of the cave art were men. Fernández has developed an objective method to analyze the paintings of hands that appear on the walls of the caves, using the new technologies and leaving aside the discharges, and has shown that many of them have been made by children.

This is the objective of the group: to develop methodologies to research also in archaeology through open science. “We are at a turning point, it makes no sense to seek answers with the methods of the past,” Garate said.

An example of this is that, as in other areas, artificial intelligence has reached archeology. Intxaurbe has reported collaborating with health research researchers: “Recently, this group has published a method to identify cancer cells and AI-infected cells. Among them is Ignacio Arganda Carreras, and we worked with them to use this same method, for example, to identify as accurately as possible who the authors of the hands were.”

The next step of the team is to simplify the processes to make them more useful and efficient. In this respect too, they believe that artificial intelligence will be of great help. “Realize that we’ve made a 3D image of a cave. Well, through an artificial intelligence program, we will be able to quickly distinguish structures and forms, such as those made by human beings, geological structures from concrete times, rock art… But to achieve this, artificial intelligence must be trained beforehand”.

The importance of social integration

Finally, they point out that 3D replicas that are made to research on the Internet can also have other uses. “In fact, the replicas we’ve created are made with all the details and can also act as an incentive for the general public,” Intxaurb said.

This dissemination also benefits researchers: “What is known is protected. For example, many discoveries have recently been made in Gipuzkoa and Bizkaia, for example in the centre of Lekeitio, in Armintxe. What happens? When the finding is reported, it has a great echo and is interested in the public. Research is being done and then, once the research is completed and the cave is closed, nothing comes to light unless a new investigation has been initiated. So over time, people are forgetting what they have under their feet, and it may happen that they think of someone thinking about making a house on top of the cave, or who knows. On the contrary, if you consider it your heritage, you will appreciate it and protect it.”

Therefore, the work carried out by researchers can be very useful for citizens to know and value heritage. It can also be used in the tourism sector to carry out replicas, as in Ekain, or to offer virtual visits. The ultimate goal is to put research at the service of society.