Penicillin Boosted Sexual Revolution, Not the Birth Control Pill

Andrew Francis is the economist who studies the relationship between the sexual revolution and penicillin. He explains that in the 1950s the expansion of penicillin caused control of syphilis, which caused a change in sexual behavior.

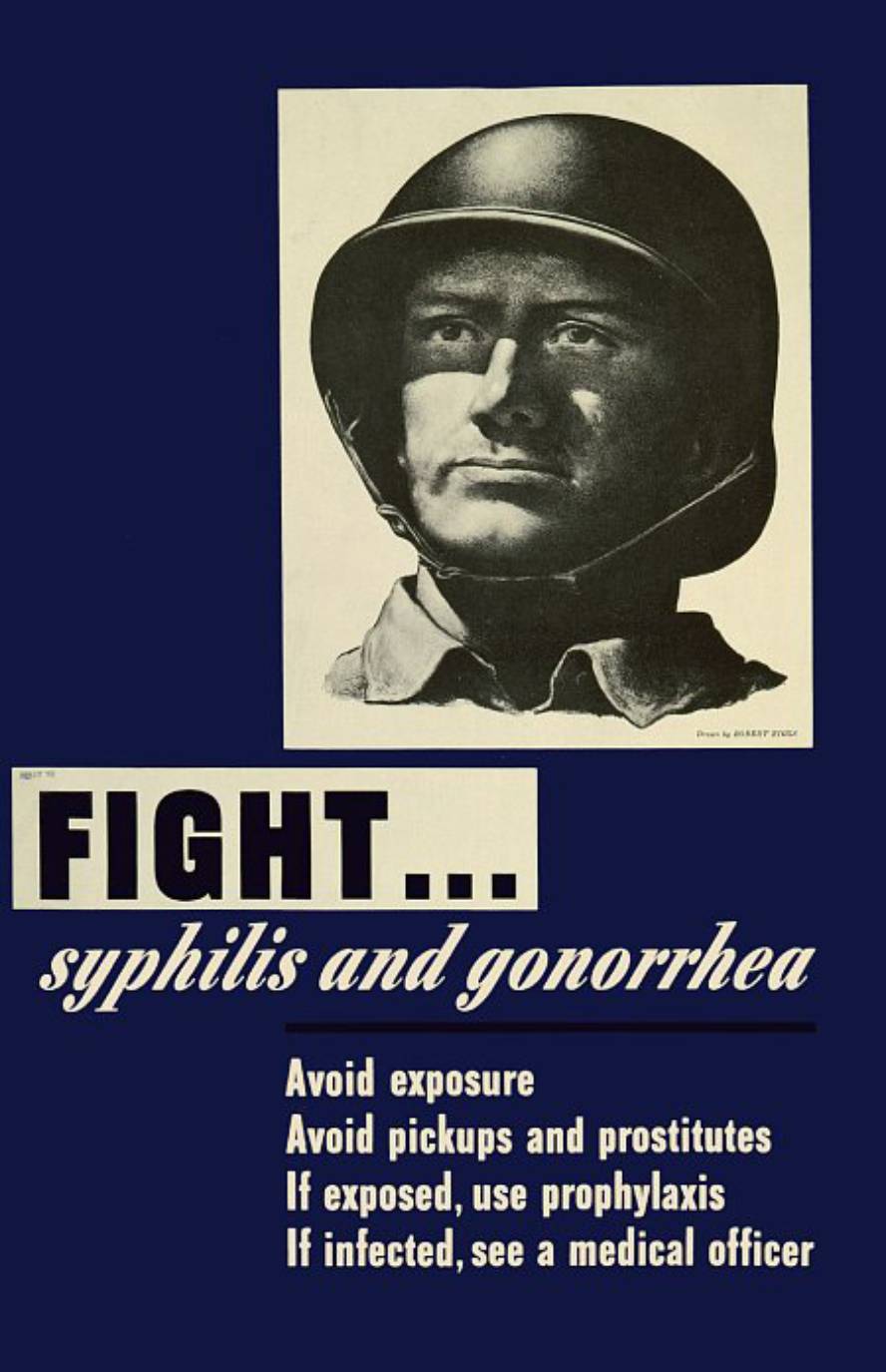

In fact, in the 1930s and early 1940s, syphilis was a serious disease: In 1939 he killed 20,000 people in the United States. “It was AIDS of the time,” says Francis.

In fact, penicillin was discovered in 1928, but around World War II it was shown to be effective against syphilis. From then on it developed, became cheaper and expanded, managing to dominate syphilis and losing the fear that people had before.

To reach these conclusions, Francis has analyzed data from the U.S. Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) between 1930 and 1970, focusing on three parameters for measuring sexual behaviors: the birth of seasonal children, adolescent deliveries, and the incidence of gonorrhea (a disease that is easily spread sexually).

According to Francis, the data highlight the relationship between penicillin, syphilis control and sexual revolution. And he has taken another step: in the case of AIDS, he has also said that the relationship between the extension of antiretrovirals and the loss of fear of AIDS should be taken into account, as the tendency to have dangerous sex increases.