Stack of brains

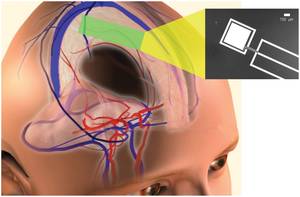

The aim of MIT researchers is to integrate into the brain and create a battery with capacity for decades. Replacing this type of current use is done in a few years. Other devices, such as cochlear implants, use external power sources to work.

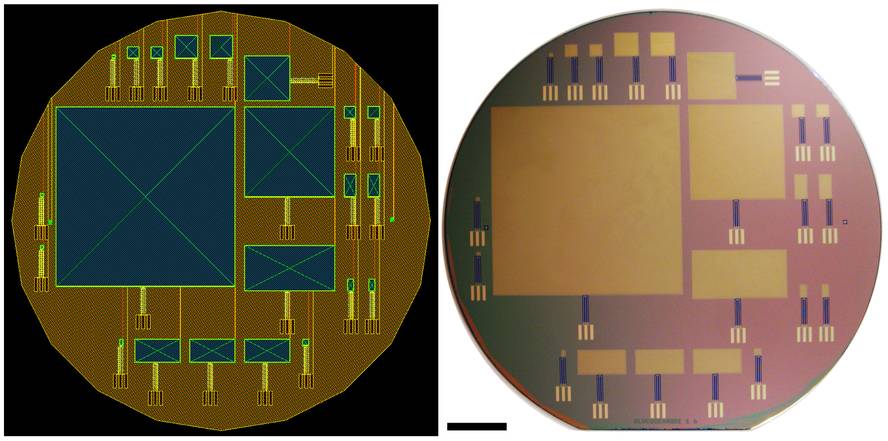

Platinum and the carbon nanotube network are the main components of the fuel cell created by MIT researchers. It is layered and shaped like computer chips.

The anode made of platinum is at the bottom and the outer cathode formed by carbon nanotubes in contact with the cefaraquídeo liquid. The greatest difficulty of the system is that the batteries are extracted from the cefardalic liquid containing glucose and oxygen, both, and that the fuels that have to react separately in the anode and in the cathode, are transferred to the places that correspond to them of the fluid they mix, without other reactions in the way and without producing short circuits that deteriorate the stack.

The design used in this case is a version of a proposal in the 1970s. The outer cathode and the inner anode are separated by a selective permeable membrane (of cation permeable nafion). Glucose passes through the network of carbon nanotubes and the membrane to the anode, where it oxidizes releasing electrons. Oxygen is reduced in the outer cathode. The electrons are directed from the anode to the cathode, closing the circuit of the electric current and by means of an oxygen gradient, oxygen is prevented from entering its interior and a short circuit occurs.

MIT researchers have demonstrated the functioning of the fuel cell in an environment that simulates the cefaraquídeo liquid and have published their results in the journal PloS ONE. In addition, computer simulations have calculated that the consumption of glucose and oxygen in the battery does not reach a quantity and speed that can cause physiological damage to the brain.

According to MIT researchers, cefaraquydean fluid is an ideal environment for fuel cell implantation: “It barely has cells, the immune surveillance is minimal, the concentration of proteins attached to the stack is one hundred times lower than in the blood or in other tissues and the glucose level is equivalent,” they explain in the article.

In fact, a lot of blood was published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society last March. The battery was inserted into a snail and used glucose from its hemolinfo to produce electricity (equivalent to human blood). According to the authors of the study, it was able to function for several months without harming the snail. The stack of MIT researchers has not yet been tested on living beings.