Bacteria also have prions

30 years ago an infectious organic system capable of reproducing without DNA or RNA was unimaginable. But prions showed that it was possible; simple proteins wrongly folded were able to infect the surrounding proteins with their incorrect folding, by contact, without the need for proliferation. Although so far only such systems have been seen in eukaryotic cells, a paper published in the journal Science shows that bacteria also have prions.

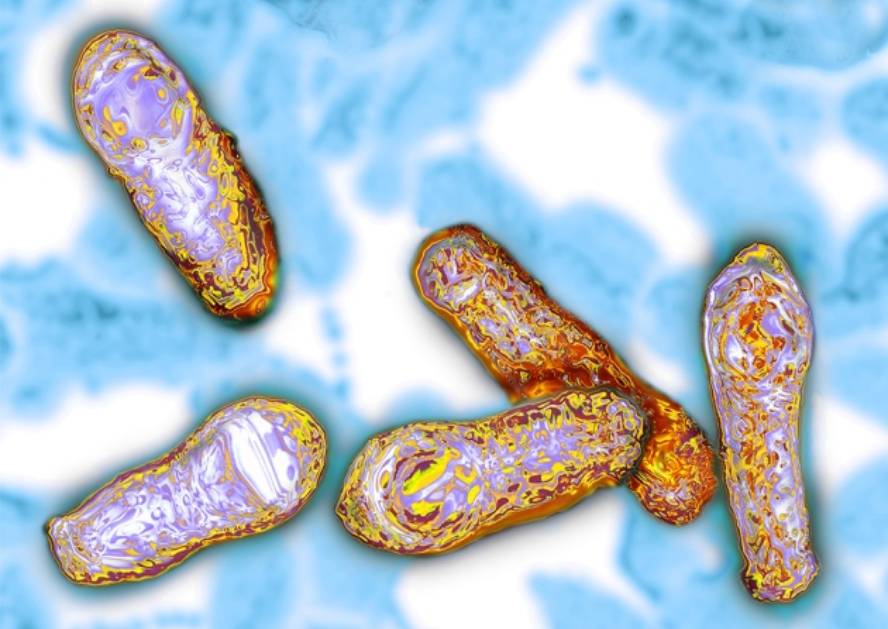

To carry out the research, 60,000 bacterial genomes were analyzed in search of genetic sequences similar to the prions of yeasts and it was found that a protein sequence called Rho could be a good candidate. Thus, it has been proven that the Rho protein of the bacterium Clostridium bolutilum is injected into the bacteria Escherichia coli and behaves like prions.

In recent years it has been found that prions, in addition to being a source of diseases, participate in other processes that can benefit cells, such as are involved in the formation of memory. They also evolve, are hereditary and control the epigenetics of yeasts.

In this case, the Rho protein is itself a component that regulates the expression and activity of many genes. By injecting the normal version of the protein Rho, they saw that it silenced the genetic activity of E. coli and that by injecting the prion version many genes were activated. In view of this, researchers believe that in the case of bacteria, by regulating genes, prions can help adapt to changes in environmental conditions. For example, the presence of an antibiotic.