Gravity affects antimatería as matter

An experiment with antihydrogen atoms concludes that gravity affects antimatry as much as matter. This is the first time the influence of gravity has been detected on the movement of the antimateria. The discovery has been announced in the journal Nature.

For most physicists, it was no surprise. Albert Einstein announced in the theory of general relativity that gravity affected all matter equally, and today there is no physical theory that predicted that gravity could be repellent to anti-matry. However, the idea was tempting because it could explain some cosmic problems, such as the distribution of matter and antimatry in the early universe, and why we only see a little antimatry around our universe, when most theories say that matter and antimatry had to be produced in equal amounts at Big Bang.

So far, the theory has never seen how gravity affects matter. No wonder, because gravity is a very weak force, the weakest of the four known forces. Despite its enormous influence on the evolution of the universe and its influence on the long distances, its influence on a small fragment of antimatry is very small and therefore very difficult to measure.

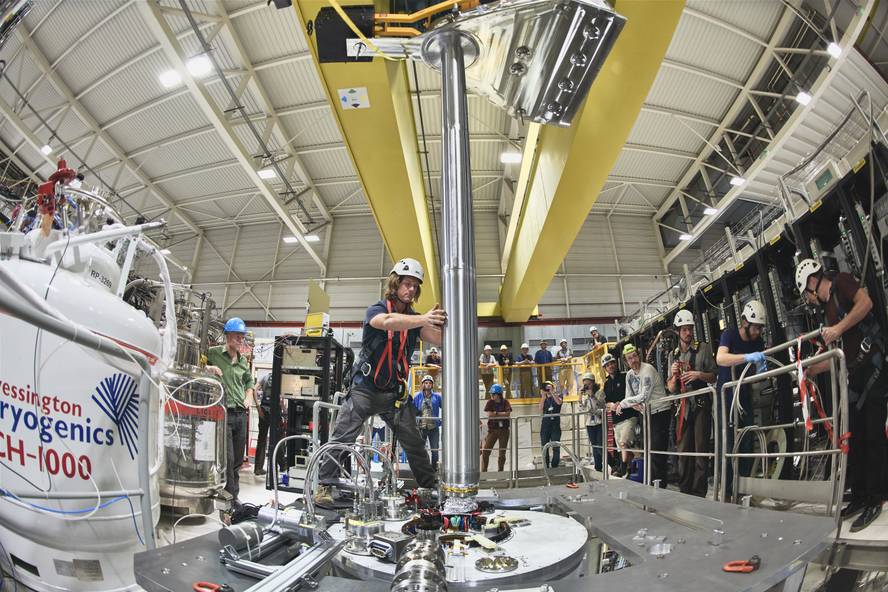

In 2018, CERN's ALPHA collaboration built the ALPHAg machine, a magnetic trap for antihydrogen atoms designed to study the effects of gravitation. The antihydrogen atoms suspended inside the device are released and analyzing their movement the influence of gravity can be deduced.

The first measurements were carried out in the fall of 2022, and what was observed through simulations and statistical analysis has been analyzed. So they've come to the conclusion that for antimateria, the probability that the effect of gravity will be repellent is so small that it's rejected. They also calculate that it is very possible that gravity produces the same acceleration as matter (up to 25% deviation depending on the results obtained). According to researchers, one of the following objectives will be to measure acceleration more accurately.