Flying in technology

To carry out a cutting-edge research with bats it is essential to use the latest technology, an indispensable condition: "The English call it cutting edge technology," says biologist Joxerra Aihartza, director of the bat research group at UPV. He has lived the process of sophistication of bat research. "Technology has made a big leap since we started 20 years ago. We have to keep working on the mountain, but more and more tools are on the back."

According to Aiartza, ornithology does not use the technology as cutting-edge as bats. "They are nocturnal, flying and silent animals for us." The sounds they emit do not hear human ears, they are ultrasound. And, therefore, the mere identification of a kind of colony requires an ultrasound detector, a device that makes the bat cry heard. It should not be a very sophisticated device, but it also joins amateur fans. But it is a representative example, not a device to hear birds, but a device to listen to bats.

Most species can be distinguished by ultrasound, but sometimes it is not enough for ultrasound to "hear," but to be analyzed. Ultrasound sonograms are collected and species are identified by computer analysis.

Technology for all

Sound analysis has been greatly simplified in recent years, as sound treatment is available suitable and quality, even for non-professionals. And not only the software, but today amateurs have at their disposal most professionals 20 years ago who did not have technology. At the same time, the technological possibilities for professionals have been greatly expanded.

"The infrared cameras we used in our day were quite special: we changed the normal cameras," Aiartza recalled. "Currently family camcorders sold in any store have an option called night shot to record in the near infrared. That also opens up many possibilities for people to do things. Until these cameras extend to the market, other technologies have been developed for researchers." Aiartza's group, for example, combines cameras that record 1000 frames per second with infrared cameras, thermal cameras.

And, for example, the use of thermal cameras has been taken to the extreme in the United States to investigate the giant colonies of bats. "Satellite surveillance has been carried out to detect the dispersion of the bat in nocturnal hunting activity in the United States. There are colonies that collect millions of bats; when they leave the cave they can be seen by thermal images taken from the satellite; satellites detect how they disperse with heat in space." This follow-up has not been carried out for the investigation of other types of animals.

This is an extreme case where few researchers have been able to use this technique. However, there are many groups of researchers who analyze bats through the usual telemetry techniques, and there have also been significant changes in technology in this field. For example, "small radio telemetry transmitters weighing a gram a few years ago weigh 0.3 grams." The bat Pipistrellus, typical of Euskal Herria, is an animal of between 3 and 8 grams, and in species of this size, for example, the weight reduction of the transmitter has opened its research possibilities.

Perhaps the greatest advances made by engineers are not related to the ecology and behavior of the bat, but to the research of physiology. How are bats? How do they fly? Can we imitate and use your recall techniques? The technology currently used to answer these questions is surprising.

The list of physical characteristics studied with sophisticated equipment is long. For example, a team from the University of Aberdeen used Doppler effect radar to investigate bat respiration, that is, to clarify the speed at which they penetrate and eject air have used a radar, in this case sophisticated technique is a great advantage, any other invasive technique. And that's just an example.

Bats in Formula 1

The reverse path also occurs; research into the physical characteristics of the bat contributes to various areas of engineering. Flying techniques and ecoenclave have aroused the greatest interest.

Bats do not fly like birds. There are big differences. Bats have very light wings compared to the weight of the whole body, shake quickly and, although at low speed, do very well. Birds generally have opposite characteristics (except for exceptions).

Lund University researchers have used wind tunnels to investigate the flight of the bat. His study highlights that bats greatly deform their wings when flying, much more than any bird. Thus they get the ability to manoeuvre.

Engineers are very interested in this research, since the research of variable forms has also become very important in aeronautics and automotive. Aerodynamics is flexible. The extreme case is formula 1, the car spoilers are flexible and change shape as speed increases. It has become a very controversial issue -- and overcoming a degree of flexibility is prohibited in Formula 1 -- because aerodynamics are very effective and increases the speed of cars and the risk of accident. But it is gaining importance in conventional cars and planes, as in addition to increasing aerodynamics, deformable parts also reduce energy consumption.

Ecofocus can also be useful in robotics. An autonomous robot could mimic the bat sonar to take over the environment. It is a very complex issue that has not yet been fully achieved. Many robotics experts have recognized that at first they have taken the idea very well, but given the difficulties involved in creating an artificial ecofocus, they resort to cameras and the usual resources of lasers.

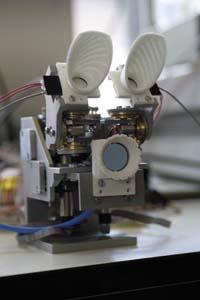

However, a team of engineers from the University of Antwerp took up the challenge and created a robotic head of a bat to create an artificial ecoenclave.

Artificial plaster

It is a CIRCE project. "The goal was to copy the operation of a real bat to the inner ear," explains Herbert Peremans. The result was a robotic bat head of 6 x 6 x 6 cm. that emits ultrasound and that, thanks to external artificial ears, receives them. "The shape of these outer ears is based on the ear shapes of the authentic bat, which mimics the interaction between sound and ear to capture or discard sound according to its orientation." It receives the echo of ultrasound through small microphones in the outer ears, digitizes them and directs them to an inner ear model to create real patterns of neurons acting.

However, the CIRCE project has not been completed. "The main challenge that remains is to make an intelligent care mechanism that leads to where to look. So, when the head is installed on a mobile robot, you can navigate through an environment. We need an eye care mechanism, and our research is focused on it," says Peremans.

In short, CIRCE engineers work looking at bats. They must compare the results of their work with the characteristics of the royal bat. This is another reason to protect bats and other animals. They are the showcase of nature's "technological" solutions. We need technology to research bats and we need bats to advance technology.