Microbiome when bacteria are easy

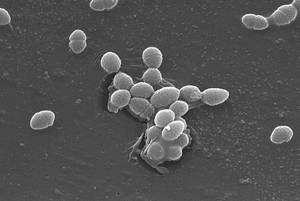

"Before we had all the bacteria and viruses as enemies and harmful, we now know that some are necessary and are part of us. For example, intestinal microorganisms are fundamental for the proper functioning of our body. These microorganisms form a microbiota community and their gene groups form a microbiome. We consider the microbiome as an organ".

These are the words of José Ramón Bilbao. Professor of genetics at the UPV and researcher of immunogenetics. In particular, it investigates the immunogenetics of celiac disease and diabetes, both autoimmune diseases. It also knows a lot about microbiosis, microorganisms that live in our intestine. These microorganisms have a great influence on both diseases. But also with the main functions of the body: metabolism, immunology and neurology. In the opinion of Bilbao, the awareness of this influence has meant a profound change of focus on medicine.

To note the importance of microbiota in our body, Bilbao has highlighted a fact: "Almost 15 years ago the human genome was sequenced. Then we discovered that this genome is not even 10% of the DNA we have in our body. The rest is the DNA of the microorganisms that live in us". And a good part of this corresponds to the microbiome, this group that Bilbao considers as an organ.

Of course, Bilbao is not the only organ that sees the microbiome, an increasingly widespread vision in recent years. For example, in 2012, the article entitled "The microbiome as a human organ" was published in the specialized journal Clinical Microbiology and Infection.

Published by the European Association of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, the authors recall that the human organism is formed by the cells of the three main groups of living beings of the Earth: eukaryotes, bacteria and arches. According to them, the bacteria form a collective functional zone in the intestine: the intestinal microbiome. They consider it an organ and, like the rest of organs, they say it has its physiology and pathology. In addition, the article deals with topics such as diagnosis and treatment.

The microbiome, an essential organ

However, it cannot be denied that this is a special organ. It weighs between 1.5 and 2 kilos, that is, as much or more as the liver of an adult. Bilbao has pointed out other particularities: "When we created, microorganisms have been in the world for millions of years. Therefore, we have not adapted to the bacteria, they have adapted to us. And in the evolutionary process of adaptation, amazing things have happened. For example, the number of bacterial genes living inside or in other animals is 300-400, while those living free in the middle are 3,000-4,000".

According to Bilbao, this means that the bacteria that live inside us cannot live alone. In fact, bacteria form communities, how the community is formed, so will their activity be. The health effects will depend on your activity: beneficial or harmful.

However, Bilbao has remembered that "by anthropocentrism or", in our culture we have been against this community, with excessive hygiene, with antibiotics... "We do not welcome ourselves as friends; we have culturally considered him as an enemy. For example, in the years 1960-1970 the antibiotic therapy was very implanted, and then it was thought that man would be able to live without any type of microorganism."

Thus, the researchers created germ-free or animal models without any microorganism, and it was observed that their life was very bad: they grew less than normal, they had a much higher tendency to develop tumors and died earlier. In Bilbao's words, "this shows that we are not born to live alone on this planet; as these bacteria need us too."

A complex community

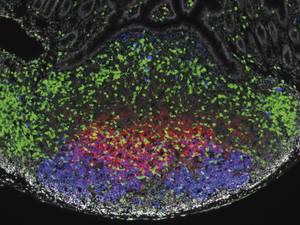

Thus, the researchers focused on the intestinal community and have shown that there are three main types, three enterotypes. This study was published in the journal Nature in 2011 with the title Enterotypes of the human gut microbiome (Enterotypes of human gut microbiome).

Bilbao explained that for this purpose the technological advance has been key. "Some species have been identified in these studies, but more than half are not identified. Studies carried out so far with microbiota or microbiome have limited to investigating only those who can grow in vitro and are very few. But with current technologies, especially with massive sequences, we can see all the genes, although we do not know all the bacteria."

Thus, sequencing the genome of intestinal microorganisms, they have found that there are three enterotypes that are not distributed by geographical areas. Each enterotype is formed by different species of bacteria, one of them fulfills the same molecular functions. This is what Bilbao has highlighted: "Although the species that compose them are different, all enterotypes have the same biological functions: protein catabolisis, ATP synthesis, energy production..."

Bilbao warns that this has consequences worthy of recognition: "For example, if we want to influence the microbiome for therapy, or if you want to transform it, we must do it very carefully, because the species that we can use in one person and another do not have to be the same, because the function that we want to complete or restore can be in the hands of different species."

This new approach, based on functions and not on species, has opened a new path in therapies based on the microbiome. However, this path continues in its beginnings, so Bilbao considers that we must "act with prudence": "At one point, it was thought that microbiome transplantation could be a good occasion to treat some intestinal alterations such as inflammation. And it has been seen that it is very dangerous."

It seems that the balance is much more complex than initially thought, although in some cases the results are being good, for example, against the bacterium Clostridium difficile, which causes serious diarrhea.

Despite the difficulties, more and more research is being carried out to know the microbiome's involvement in metabolism and, among other things, to take steps to understand obesity. For example, the article "The intestinal microbiota and obesity" was published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology in 2012. In the study, it was shown that microbiomas of thin and obese people are very different from each other.

What's more, the researchers infected mice without microorganisms with bacteria from each other, and found that mice that collected dominant bacteria in the intestine of the most obese people, the Firmicutes family, accumulated more fat in the body than the rest, although all had the same diet. Although there are still many questions left unanswered, some of them are gradually clarifying.

Professor of the immune system

Important steps are also being taken to know the relationship of the microbiome with the immune system. Bilbao recalled that the immune system is the "most important weapon" against cancer and highlighted the large participation of the microbiome in its formation.

"The antigens of microorganisms excite the immune system and this excitation shapes its response to some and other stimuli," explains Bilbao. In general, the answer may be: acceptance or opposition. But things are not so simple: "This decision does not always depend on the antigen, the medium influences the response and changes the response regardless of whether there are microbes in the medium."

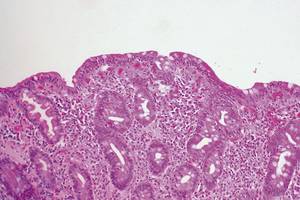

The great influence of intestinal microorganisms is not so surprising if we take into account that the greatest interaction of our body with the external medium is through the intestine. And the first contact with new antigens also occurs in the intestine. Therefore, one of the functions of the microbiome is precisely that: excite and keep alert to the immune system.

Another function is to occupy the place. In fact, thanks to the microbiome, the intestines are ingested and when an ecological txoko is full, it is very difficult to colonize them by other bacteria.

However, Bilbao recognizes that there is a risk of infection: "In fact, the bacteria that form the microbiome have very few genes, they are very vulnerable. Therefore, the situation is similar to that of the Amazon: it is very rich according to the diversity of species, but if one disappears, the balance is lost and its recovery is extremely difficult. The same thing happens to the microbiome". That is why it is so important to maintain balance.

Error in response

Bilbao, as an autoimmune disease researcher, has also referred to them: "The education of the immune system is key to adapting our response to certain situations. And in autoimmune diseases, both in celiac disease and diabetes, and in many others, the error does not exist in the organ. That is, in the case of celiac disease, what is wrong is not intestines or areas in diabetes, or in the case of arthritis, the joint. No, the failure is in the immune system."

According to him, this error is in most cases the inability of the tolerant response, that is, the inability to accept own proteins or structures. "In this regard, the feeding and correct management of the antigens that enter through the intestine are those that have the greatest influence".

He has also given some examples: "Various studies have shown that feeding, immune system responsiveness, and the risk of developing an autoimmune disease in the future are related. For example, in research mice in diabetes, it has been observed that the administration of non-digested soy proteins or cow's milk albumin accelerates autoimmune processes. These antigens enter the intestine and confuse the immune system. Why does that happen? Because they have not been managed properly, because microbiomas have not been reduced well and have been shown well so that the immune system can give an adequate response."

This has to do with the progressive introduction of food into the diet of young children: "In addition to the metabolic capacity of the child, it has a lot to do with the education of the immune system," explains Bilbao. "As your microbiota develops, new antigens can be incorporated, so that your immune system is preparing to have an adequate response to these antigens." Therefore, the diet and composition of the microbiome are directly related to the risk of developing autoimmune diseases. And in the diet, besides food, there are two other keys: how much and when.

The final goal would be to cure the disease through treatments based on the microbiome. However, Bilbao has acknowledged that they are still "far away" from achieving it, even though steps are being taken: "In diabetes they have seen that the development of the disease is directly related to certain microorganisms. Then, it seems that it would be possible to adapt the microorganism community to promote a tolerant response and avoid the appearance of the disease." But the cure of diabetes is a little further away.

This line is also being investigated in celiac disease: "Right now, at the European level, gluten is being investigated, the toxic protein for celiacs, the best time to manage it for the first time. It may take too soon to be counterproductive, increase the risk of celiac disease, but the same can happen later. It is fitting, therefore, to define the appropriate time to make this new antigen known".

Bilbao, however, goes beyond: "In this sense, microbiosis has much to do with: if we knew which bacteria are mixed in this process, we would have the opportunity to predict suitable bacterial populations to children, thus avoiding further problems in the management of antigens." But it is prudent. In fact, he has said immediately: "But that's a matter of the future."

Neurology, hidden relationship

Although all these investigations are relatively new, the most recent can be those carried out in neurology. Among them are studies that analyze the relationship between autism and the microbiome, as published recently in the journal Cell: 'Microbiota Modulate Behavioral and Physiological Abnormalities Associated with Neurodevelopmental Disorders'.

According to the researchers in the title, the microbe is able to model anomalies related to alterations of neurological development. In fact, they have shown that mice with behaviors related to autism present errors or imbalances in the intestinal barrier and in microbes.

From there, the following experiment has been carried out: they have supplied mice with a bacterium, Bacteroides fragilis, which lives in our intestines. It has been observed that the intestinal barrier is recovered, the microbiota is balanced and behavioral problems are reduced. In addition, it has been confirmed that changes in metabolites also occur, hence some intestinal bacteria have important functions in the metabolism and influence neurological development.

This experiment is not enough to think that the same can happen in people, but they are being investigated further on that path. According to Bilbao, many of these studies show that the microbiome has much to do with the ability to respond to external quinadas, which are precisely those that have autism that have a lack.