Investigating the Key Factors for the Conservation of the Pyrenees

Zoologia eta Animalia Zelulen Biologia Saila, Zientzia eta Teknologia Fakultatea (EHU)

The Pyrenean or aquatic mole, Galemys pyrenaicus, is one of the most unique animals in the Basque Country. This intective mammal, endemic in the north of the Iberian Peninsula and in the north side of the Pyrenees, belongs to the family of the talpids (mole) and inhabits rivers and clean streams. Despite its antiquity known for its morphological and taxonomic peculiarities, its low population density and hidden life make many of the aspects of its biology fundamental to its conservation still unknown.

In recent decades, the area of distribution of the dismantling in the peninsula and in the north of the Pyrenees has been reduced by more than 50%, which has meant its inclusion in catalogues and red bands of threatened species (Fernandes et al., 2008). The most surprising thing is that rivers that have apparently achieved a better state of conservation over time have seen a decrease in population. There is no clear diagnosis of causes that impedes the design of effective management plans. The fragmentation of metapopulations, habitat degradation and scarcity of pastures are the possible causes of this decline (Nores, 2007).

The demise of the Pyrenees, our secret treasure

Muzzle is the most characteristic anatomical structure of this animal because of its compressed horn appearance. Rounded body and long tail, crushed laterally on the distal side. Its extremities are equipped with thick claws to maintain the underwater substrate. The front legs are short, with small interdigital membranes, while the rear legs are long and large, inclined inward and with large interdigital membranes, with swimming function. The color of the body is brown, but under water, reflects metallic glitters of bronze or silver, thanks to its peculiar type of hair. It has blackish horns and flesh tail.

The living area of this nightlife animal ranges from 450 to 600 meters (Nores, 2012). The main key factor for life is the regular flow of water throughout the year, so it prefers oceanic to Mediterranean climates. Its presence, rather than altitudes, is conditioned by the slope of the rivers, the depth (< 70 cm) and the speed of the current. It prevents contaminated water, although it is able to withstand low levels of pollution. In general, thick substrates (especially reefs and rocks) predominate in the habitat of the slope against the fine ones, being hardly observable in areas dominated by clays.

The zeal takes place between January and May, and the breeding season extends from April to mid-August (Richard, 1976). Ages range from 1 to 5 young and fashion is 4 (Peyre, 1956). Females have a postpartum stratum, so they can have more than one breeding throughout the year. You can reach sexual maturity with one year.

As has been observed in the morphological study of fecal residues (Bertrand, 1993), it feeds on benthic macroinvertebrates of relatively large size and low degree of clerification, mainly larvae of tricopters, plekopteros and ephemeropters. Among the catches are species sensitive to pollution. This indicates that the sensitivity to contamination of this animal depends mainly on its prey, rather than its own.

The main threat factors of the Pyrenean demise are (Nores, 2007): fragmentation of populations, reservoirs and power plants, canalizations and civil works, increase of human populations in urban areas of the mountains, degradation of the bentos, diversion of water, destruction of margins and river forests, chemical and organic pollution of rivers, water sports and extraction of arid.

With our research, what?

The general objective of the research being carried out in the Department of Zoology and Animal Cell Biology of the UPV/EHU is to know the key factors that condition the spatial and trophic ecology of the pyrenean demise, still unknown for its scientific interest in the management of this threatened species. It is being studied, by combining different approaches, what conditions the selection of habitats of this animal at the level of microhabitat and whether its diet is generalist or specialist. The ecological wealth of the habitat can play an important role in all of this. Therefore, we have worked on two ecologically different rivers taking advantage of the LIFE+ ZABALIBAI project: In the Elama river (Urumea basin, Navarra) and in the Leitzaran river (Oria basin, Gipuzkoa). The Elama River is among the best preserved in the Basque Country, as there has been hardly any human activity in its basin in the last almost one hundred years. The Leitzaran River, on the other hand, is in good ecological condition, but is affected by numerous hydroelectric plants, with a flow of drought much lower than the natural flow.

Our hypothesis is that the Pyrenean demise will optimize the diet and habitat use depending on the availability of the resources it finds. These resources can be both trophic (potential prey) and other physical resources (potential shelter) that offer animal safety. The identification of these limiting resources will be essential for the execution of any management project aimed at the conservation of the species.

Habitat use

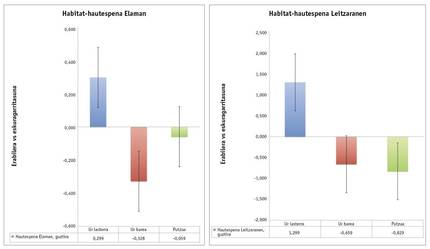

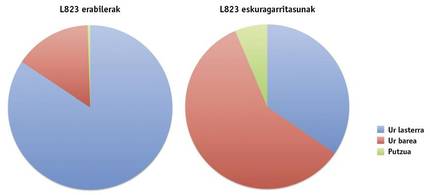

Combining captures, radiotelemetry tracking of specimens and spatial characterizations of hunting microhabitats, we have been researching in the field of spatial ecology. For this, in the months of September and October 2016, we caught the hocinos with platforms, alive and without discomfort (Gonzalez-Esteban et al., 2003) and in addition to taking sex and age data, we paste small radio emitters (< 2 g) into the coat. After two or three nights of catches, 31 levels were followed (15 in Artikutza and 16 in Leitzaran), each of them from 3 to 5 nights. To determine habitat selection, the map of accessible habitats was constructed (characterizing fast water, calm water and wells depending on flow) and the locations of the 5-minute follow-up points were analyzed. Taking into account the active permanence time of the overflows in each type of microhabitat and the relative abundance of the different types of microhabitats in their area of life, we define priorities based on habitat and study selection.

Interim analyses of habitat selection have suggested that the water moss, during the time it remains active, opts for fast water along with calm waters and ponds. This selection would increase the number of fast waters to ensure the survival of this vulnerable animal. It should be noted that the selection index has a higher value in Leitzaran than in Elama (0.299 in Elama, 1.299 in Leitzaran), suggesting that in Leitzaran, in general, the conditions are worse.

The differences between the Elama and Leitzaran rivers would be related to the characteristics of the channel. The Elama basin presents an excellent state of conservation, covered by mature forests and with little human incidence in the channels. In Leitzaran, however, there are numerous forest farms and forest tracks that only increase the impact on the river by hydroelectric plants, reaching in styling to eliminate more than 90% of the total flow. The reduction in the flow rate means a reduction in the number of fast water per surface unit (Arroita et al. 2017), and thus, according to the results of this study, it focuses on the spatial ecology of the aquatic environment. Next year, studies will be carried out to determine the effect of water flow variations on modeling, in order to analyze in more detail the effect of water extraction from hydroelectric power plants in all this.

Diet analysis

Once habitat selection is known, the next objective of the study will be to know the selection of diets. The objective of the immediate future will be to know the trophic ecology by molecular analysis of the diet (DNA study of stool with NGS) and the cession of food availability in each microhabitat.

To determine the availability of fodder, macroinvertebrates (insect aquatic larvae) were sampled and identified at the same time of follow-up. At the same time, for the determination of the diet, more than 100 fresh excrements were collected throughout the research area of each river to reflect the diet of the greatest possible number of hocinos. Molecular analysis identifies the prey that appears in the feces (with the IOC gene), after refining the methodology through a previous pilot study.

Once the available prey community is known, and taking into account the results of molecular stool analyses, a comparison will be made between them and information on the dietary selection of the collapse will be obtained.

Key factors for conservation

After analyzing the habitat and diet selections of the Pyrenean desman, the final objective of the study will be to determine the limiting resource. To do this, microhabitat selection patterns may refer to the availability of local dams or other environmental factors (shelter availability, hydrological, physical factors, etc.) we will specify if you are followed. All this will allow to define the key directions for the management of the Pyrenean demise.