Mathematics, a tool to know the brain

"I am the result of the functioning of my brain," says mathematician Pedro Larrañaga. He is working on two projects with the aim of knowing the brain and in recent years has changed the way we see: "At the beginning of bioinformatics we thought we were the result of our genes. Now, however, University researcher Sebastian Seung Princeton, entitled "I am my connecctome", claims its connectivity. I would say that we are the result of brain functioning."

For Larrañaga, the brain is the most "mysterious and complex" organ in the body: "It weighs about 1.3 kg and has 85 billion neurons and there are billions of connections between them." In his opinion, he defines the functioning of this complexity.

It does not deny that genes also make us, "but also the experiences we live". It relates to the Bayesian vision of the world: "In statistics there are two perspectives; one is the so-called frequentist and the other is the Bayesian. And today the vision of the brain is being imposed as a Bayesian machine. Because in statistics, having a Bayesian vision means that when you have a problem, not parts of zero, but always have a background. That is, if a priori you have a knowledge that can be modified with the data collected, with the experiences lived. Then, a priori they become a posteriori ".

According to Larrañaga, this cycle is lived uninterrupted. Faced with another problem, a posteriori, these are a priori and can also be modified as a result of evidence or experience. "And this has to do with our vision of ourselves. We at first have genetic information, but education and life experiences make the result fit."

With this vision, Larrañaga works on the two projects involved in the study of the brain. Cajal Blue Brain, between the Polytechnic University of Madrid and the Cajal Institute of the CSIC, and Human Brain Project, at European level.

They say that it is all that bears name

The Cajal Blue Brain project is led by Javier de Felipe, researcher at the CSIC Cajal Institute, and Larrañaga, head of a module. It is a ten-year project, already in the center. They do basic science, that is, they do not seek direct applications, but know. "We do neuroanatomy and study the skin columns of the brain, the cortex," explains Larrañaga.

They collect and analyze information about all elements of neurons. He points out that currently they cannot access this information in bulk. "We do a different job than Americans. They want to develop neurotechnology and ultimately get technological tools that allow massive data collection. They have great interest in electrophysiology, that is, they want to see how likely the neurons in the environment are activated when a particular neuron is activated. For example, the Allen Institute is in that."

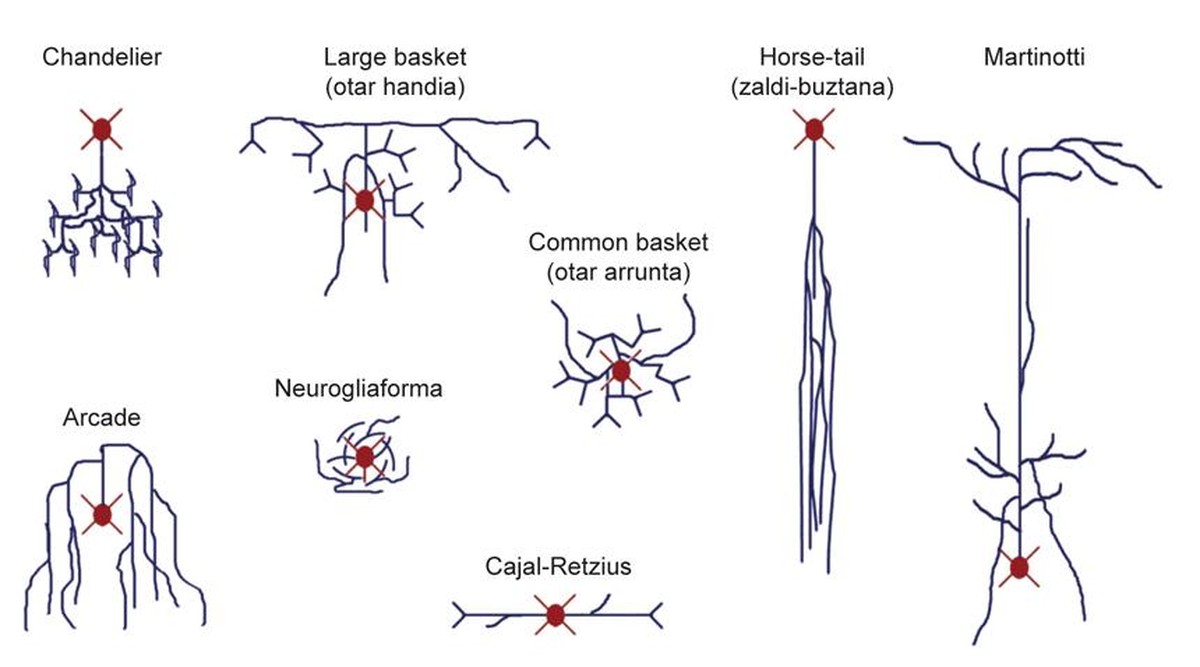

However, in Cajal Blue Brain they have taken another path. In fact, their objective is to automatically classify neurons using morphological measures and they have already published articles in this regard, such as an analysis published last year in the journal Nature Reviews Neuroscience, entitled New insights into the classification and nomenclature of cortical GABAergic interneurons.

According to Larrañaga, a Basque saying adequately reflects the idea behind it: "They say it's all that's named." The prestigious neurobiologist Rafael Yuste has also used this saying in his articles and conferences, "and that's what we want to do, to name neurons."

Ratings, designs and forecasts

There are two types of neurons, pyramidal and interneurons. Pyramids are similar to each other, interneurons are very varied in appearance. "That's why it's not easy for everyone to use the same name because we don't all sort them the same." In this sense, he considers the analysis published last year to be of great interest and usefulness. "We have created clusters, that is, we have grouped those with similar characteristics, into one group, and those with other characteristics in another group, and thus we have created a classification system."

In addition to classifying neurons, Cajal Blue Brain aims to answer a question: Does the brain have an optimal design? "According to biologists, the brain is designed according to standards, including the minimum length of dendritic trees. We have tried to prove it with artificial intelligence techniques and, according to our studies, it is not entirely optimal. And with a machine we have achieved a better result than our brain. Therefore, we have room for improvement," Larrañaga said in a joke.

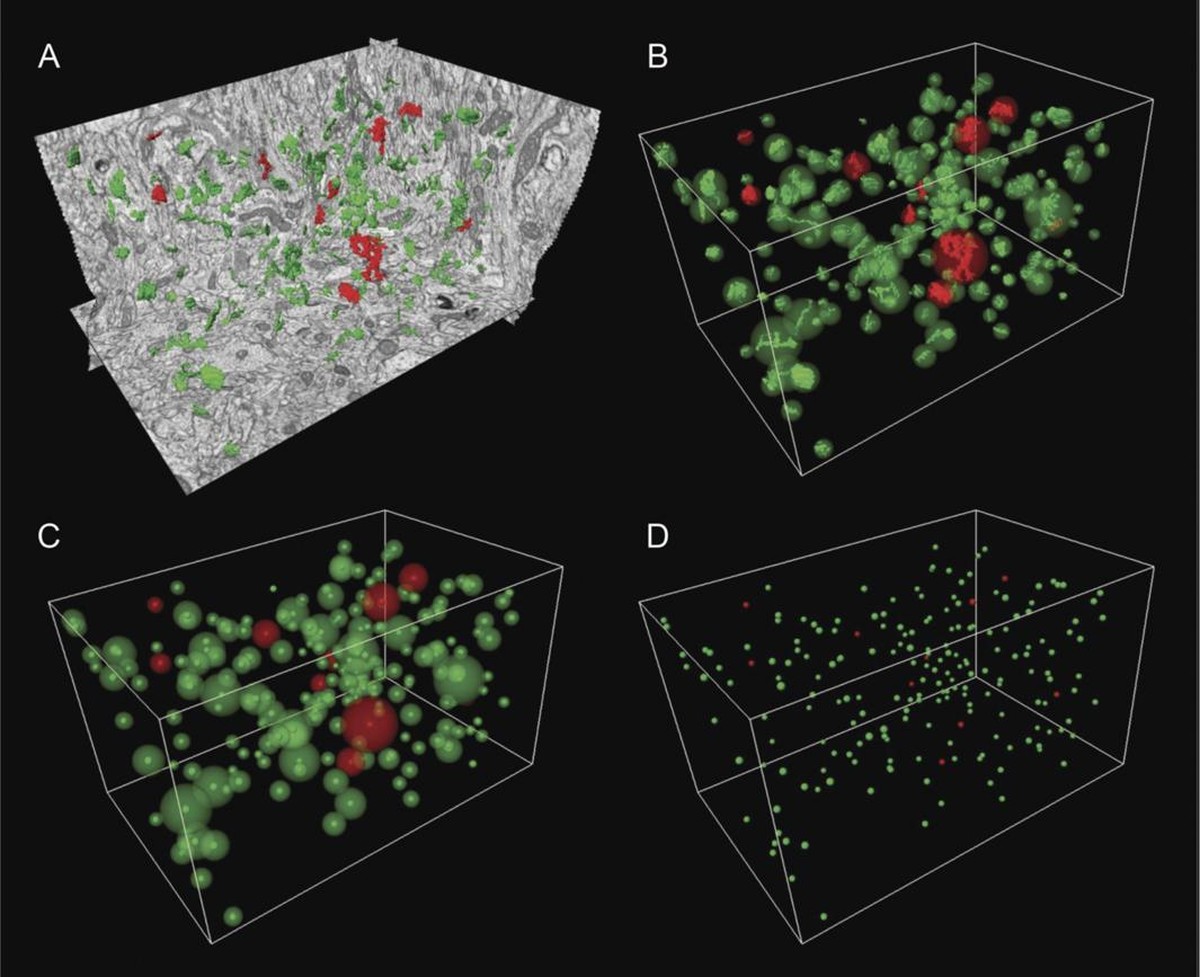

On the other hand, it has also been studied whether the synapses are organized randomly or according to a specific model, and they have seen that the location of the synapses is not entirely random, that behind its location there is a mathematical model. In addition, the types of dendritic thorns have been classified. "With dendritic thorns we have done the same thing as with Internet clusters. We have researched more than 8,000 thorns, collecting from their image 50 variables or parameters and proceeding to their automatic classification. Although three types have so far been distinguished, we have distinguished seven types by mathematical models."

Larrañaga anticipates that this work will be published soon. He also warns that only the neurons of two people, one of 40 years and one of 85, have been analyzed, so that the results are more consistent, they must conduct the same research with more people. However, researchers have seen that the distribution of plums is not the same in these two people and believe that age may be related to it.

Finally, the Cajal Blue Brain project also investigates predictive neuroinformatics. According to Larrañaga, it is about checking if they are able to predict the electrophysiological behavior of a neuron based on its appearance and genetic characteristics. "Our goal is to see if there is a relationship between appearance, genetic characteristics and electrophysiological behavior in order to make predictions."

International cooperation

Pedro Larrañaga works not only at Cajal Blue Brain, but also at the European project Human Brain Project. The mathematician has defined it as a "giant" project: "Tell us: The European Union should select two priority projects for the next decade. For one is graphene and the other is the brain. It was announced in February last year and will last until 2022, where we are working more than 85 organizations and more than a hundred laboratories."

It has three main objectives. The first is to know the brain, the second is to investigate neurodegenerative diseases and the third is to develop neuromorphic computers, supercomputers that mimic the functioning of the brain. "The problem is that supercomputers have poor energy efficiency compared to the brain. So the third goal is to find a solution."

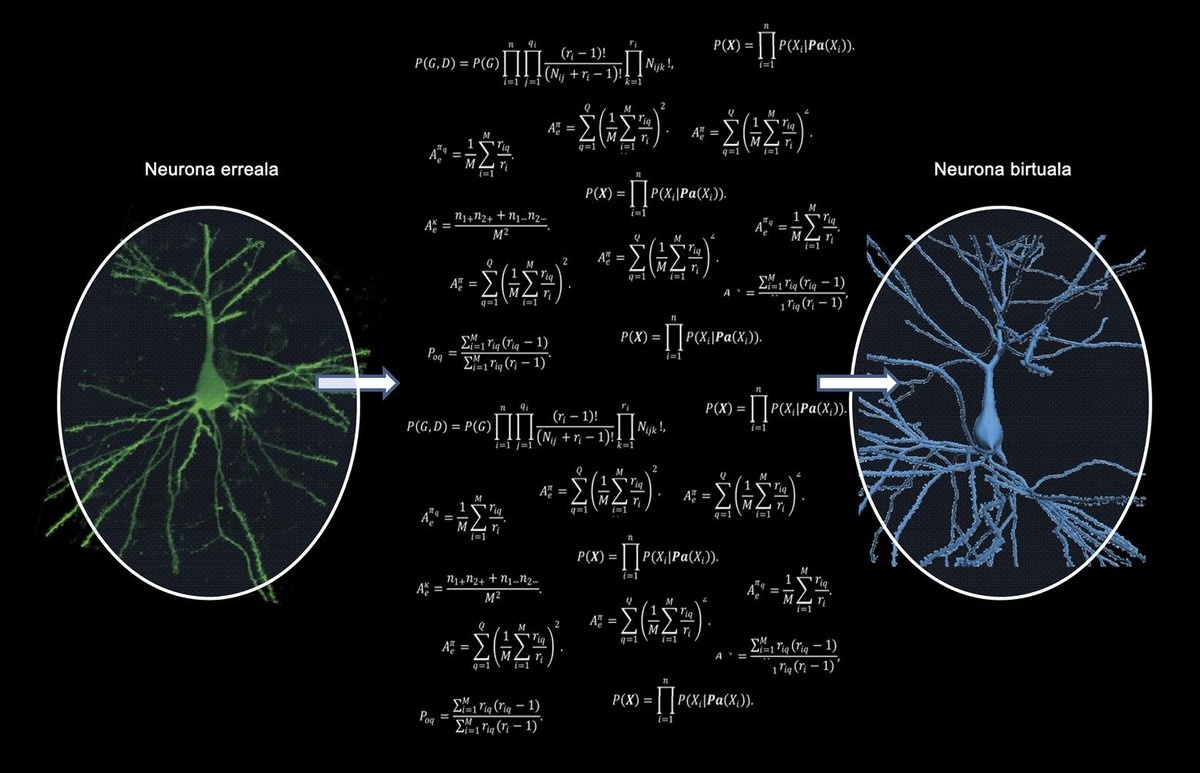

The Larrañaga team works on their first goal. He explains that there are eleven subprojects within the Human Brain Project that lead the fifth, the neurocomputer subproject. This is how he explained his work: "Our mission is to develop mathematical-statistic-computational tools to convert the data provided by biologists into mathematical models."

Thus, they work with pyramidal neurons: "We investigated interneurons at Cajal Blue Brain and here pyramidal neurons. Specifically, we have to make a mathematical model for pyramid neurons. And there we are."

In Human Brain Project, in principle, the ideal would be to collect and integrate the information obtained by all working groups. However, Larrañaga does not believe that it is easy, partly because it is difficult to coordinate and unify so many research, but especially because it requires cultural change in some areas of research.

According to Larrañaga, "we are used to publishing our data and others doing their research. However, neurobiologists do not have that culture, they keep the data they get for them. And that's a big obstacle to moving forward." In any case, Human Brain Project is in its beginnings and will give much to talk about in the coming years.