Mars, old and new

The Planetary Report: It is clear that, according to the information received from the data sent by Mars Global Surveyor ( MGS), a “new Mars” is being created. To what extent has your vision of Mars changed?

Bruce C. Murray: Mars Global Surveyor has brought to me a new concept of Mars, the territory of broken paradigms. The MGS has not only given us amazing results, it has taught us that we cannot do it.

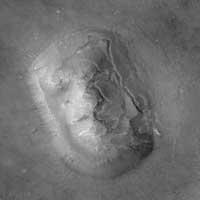

If you analyze Mars closely, you won't see what you expected. I'm going to give you an example: we all believed that the earth's surface of the south pole of this planet, the place where the landing of the Mars Polar Lander was expected, was going to be smooth, as the studies carried out so far showed. So you can imagine the surprise we took when the first photos of Mars Orbiter Camera (MOC) showed us a granular, toothed surface. We do not know the causes that have originated them and there is no earthly analogy to explain it. It is clear that in the polar territories of Mars there is some process that we do not understand.

On the surface of the Moon there are a few morphological characteristics that are not easily explainable with the impact. The moon has a layer of spill that grows one meter per billion years thick. Therefore, the 3,000 million year old “tide” (volcanic plains) of the Moon has a 3 meter thick spill layer. We know that this can be seen in the layers of impacted craters. But to our surprise, Mars has no layer of landslides.

Pathfinder arrived on Mars in 1997 in search of erosion caused by ancient floods. On the surface were identified the sedimentary traces that left the huge floods that occurred a billion years ago, as if they were produced yesterday. Today this seems surprising to us. It was then explained: “Well, there will surely be some residual dune that would protect this area and disappear later.” Now, however, the photos of the MGS and, above all, the MOC of Mike Malin show many other areas of the planet where there are no regoliths.

Besides not having the regolith, Mars has few small craters. It seems that something has been protecting or scratching the surface, but we don't know what it is. And the explanation of the above-mentioned dune protectors does not serve the entire planet. So what is the answer?

I will mention another broken paradigm. As the MGS had a problem on a solar panel, it closed the orbit and took a year to switch it to a circular. During this time, the spacecraft approached much to the surface of Mars, 150 kilometers from its surface. How important is this? Above all, the results obtained by the magnetometer and the electrometer inside the container caused curiosity.

The magnetometer measures the force of the magnetic field and the direction of that force. The electrometer, on the other hand, measures the direction of electrons, charged particles, towards the system. This is very important, since in addition to the magnetic field you get the direction of the electrons at the height you are measuring. This way you can know where the electrons come from and, to some extent, rebuild the lower area. But this can be done when you are under the ionosphere, above the ionosphere, because electrons cannot pass.

Very good data were obtained, but then we realized that there are great irregularities on the surface of Mars. At the top, say about 200 or 300 kilometers, we saw that surface magnetism occurs, which is surprising. On the one hand, because these irregularities are terrible – the size of the irregularities of the rocks of the earth's surface 10-100 times – and because we have no idea what it causes on Mars. On the other hand, irregularities, especially for being in the southern hemisphere, not in the north.

On the other hand, we have Hellas, a huge basin with almost 2,000 kilometers of width and without irregularities. According to an interpretation, Hellas is more recent than the phenomenon that caused the irregularities. It is possible that by creating the Hellas basin, shocks and heat demagnetize the surface of the area. The problem is that Hellas is about 4,000 million years old, which means that irregularities are even older. That is still more mystery.

TPR: What have the data provided by Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter (MOLA) added to the new vision of Mars?

BCM: What was done by the MOLA is the following example: Carrying out a detailed topographic map of all terrain. In addition, the MOLA is taking data uninterruptedly, day and night, in each orbit. From there we have obtained a lot of data that we are analyzing. Right now, at Caltech (California Technology Center) we are using topographic data to find new craters, i.e. craters that cannot be seen in wide-angle images of Mariner, Viking or MOC cameras.

What have we found? The Hellas basin is much deeper than we think. But if you are 4,000 million years old, as we calculated, how has it been empty for so long? The Marineris valley is also deeper than expected.

However, the most surprising fact is that the North Pole basin, an impressive terrain, in addition to being very deep, as expected, is totally soft. Many say: “Here there has had to be a mass of water” I’m not very sure, but I think the liquid water of Mars came here and accumulated: the southern hemisphere is bigger than the north, and in all points of the south to the north there are traces of ancient water. Therefore, water had to go to the northern pole basins. Therefore, it is now quite evident that on Mars there was a lot of water. However, we still cannot explain what happened to that water or how it can be exactly.

TPR: Do you think Mars may have a temperate, humid or Earth-like climate?

BCM: I see no evidence that it had an environment similar to that of Earth. Although there was a lot of water on the surface, I think it was covered with ice. Were there potential habitats of life? Who knows?

Through Mariner 4 we know that Mars has large craters. They will be between 3 and 4 billion years old, and the smallest are like moon craters, in the form of a cup, with sharp edges. The Meteor crater of Arizona, of only 20,000 years, has already had a low lake and has suffered erosions. However, the craters of Mars seem newly created.

Therefore, the traces of craters show that Mars has never been like Earth. However, immense remains of water can be observed, as if the water was still there. However, we cannot say what happened to the water, but we know that in the polar territories there is not enough space for the water to be now as a layer of ice. There are still many mysteries.

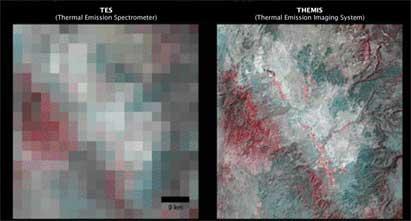

TPR: What do you think about the hematites detected by Thermal Emission Spectrometer (TES)? (The hematites are formed by oxidized iron and are normally formed only with liquid water.) Isn't that the sign of a more temperate, more humid climate?

BCM: TES had a hard time getting into the atmosphere to take traces of a mineral hard to detect on the surface. TES detects thermal radiation and then tries to obtain its spectral traces. This is quite difficult on the Moon itself, as there is no atmosphere. Also, if you have an atmosphere with carbon dioxide, dust and water vapor, it is still more difficult. Therefore, the TES team has worked hard to generate atmospheric emissions and transmission models. They have already found something. On the one hand, the dark areas of the northern hemisphere, apparently lava, are richer in silica than the alleged lava areas of the southern hemisphere.

That's good news, because it's hard to get something so rich in silicate on Earth without tectonic plates, and we have a good proof that tectonic plates have never existed on Mars. Once again, on Mars there has been a supernatural process that we do not know, leading us to geological and chemical separation.

Hematites are constantly formed on Earth, ships, pipes, etc. Any material with high iron content arises from interaction with water and oxygen over time. The most surprising thing is the detection of hematites on Mars, an oval shaped area equivalent to 300 kilometers of surface. What can be the reason? Does it come from a lake?

TES has made two discoveries: on the one hand, hematites, which needs moisture to complete and on the other, feldspar. The latter would not be if there was moisture. Despite this, there are still those who say that on Mars the climate was hot, humid, but for me it is another mystery, another broken paradigm.

TPR: Describe your vision of the future exploration of Mars.

BCM: I compare the exploration of Mars with the historical exploration of Antarctica. From my point of view, the first exploration of Mars was telescopic, which, compared to the Antarctic experience, was the best possible. This is what Captain James Cook did when he crossed the frozen continent along the coast and discovered that there was land mass there. The next phase began with Mariner 4. It was the beginning of a very primitive robotic exploration, which was followed through the MGS and the missions of the coming decades.

All this can be compared to other actions such as the first arrival of whale fishermen to the coast of Antarctica, in which a camp was built at McMurdo station with the first humans who arrived there, from where the expeditions were organized inside. These did not initially have maps covering the entire area. After World War II, the United States first achieved accessible technology to traverse Antarctica through the air and explore the continent through the air. It is currently done via satellite.

Antarctica reached the occupation of the first human beings in 1976. Thus, in the case of Antarctica, explorations lasted between 80 and 85 years before the beginning of human occupation. In the exploration of Mars, we have to start counting on Mariner 4, in 1965, and I would not be surprised that the first man did not reach the surface of the planet until at least 2030.

Today, in 2001, the best thing we can do is to do more real explorations. This, in the case of Mars, means organizing a Mars Discovery Program. NASA has just unveiled the Scout mission, planned for 2007. There are already 50 groups that have submitted their research proposals and unfortunately only one of them will be selected. At the moment there is no vision for another Scout mission.

All this is a source of joy that until Mars Polar Lander's failure in 1999 there was no other exploration like the Scout mission. Sampling and technological development were the factors driving this intention. The balance has changed now, but I thought it would change more. I hoped there would be a Scout mission in each of the launch options, i.e. every four years without precision. For now, however, we know the unique release. At this point it is clear that the scientific interests around Scout do not coincide with the usefulness of NASA flights.

TPR: He mentioned the idea of the bases of Mars that we exposed in our previous issue. Can you tell us your opinion about a base program?

BCM: The idea of establishing a basis for the exploration of Mars would somehow compensate for the imbalance between two groups: those who seek human mission and those who believe that robotic exploration is a threat. We need both: the dream of human exploration and the practical demonstration of that dream. I don't see men in space suits coming down a rope in the Marineris Valley. I see the symbiosis between humans and machines. The plan of a base allows it.

We are in a process of exploration comparable to that of Antarctica. The human factor has not changed. There is no more daring astronaut than Ernest Shackleton and with so many resources. Machines are getting better, especially information technology. All this allows to carry out the effort, but future explorers of Mars will have to solve it well with the machines.

TPR: To tell something else? More broken paradigm?

BCM: With MGS we've got a lot more data, better and better tools than ever, but we still know less. How is it possible?

We believe that the knowledge we had is not correct. We were deceived and I am to blame. I have been one of the conspirators in the process of misinterpreting what we have seen. I didn't understand the complexity of the Mars processes well, I was thinking in a simplistic sense. However, he was among the good companions.

MGS is a perfectly elegant mission. The data obtained in it will probably be the ones we have on Mars for the next 30 years. But the NASA program at this time is based on the pre-existing objectives of the MGS.

We are at the beginning of the exploration process, more backward than we think, which means moving forward with exploration and working as hard as possible.