Ice, water and fire Galileo's European Mission

Imagine as you explore a world in extreme conditions, in which the intense cold of space turns water into fragile ice and poured the molten stone under sources of sulfur. In your liver, suspended from space, there is a big bright balloon, with storm clouds in column form that change shape in a few hours.

The Galileo probe has undertaken the European Mission (GEM) of Galileo. In the vicinity of Jupiter, he will do two more years and analyze ice, water and fire: The ice surface of Europe, the lightning storms of Jupiter and the volcanic bases of satellite Io.

Galileo arrived at Jupiter on December 7, 1995, after a six-year journey from Earth. Io passed through the surroundings of the satellite, the main motor lit it and brake to get a proper orbit. Galileo obtained wonderful data through the probe that launched into the atmosphere on Jupiter and the two-year mission, 11 orbits around the largest planet in the Solar System, has revealed fascinating details about the planet and its satellites.

For example, although the main components of Jupiter are hydrogen and helium, there is also water. The water is found in the highest layers of the clouds of Jupiter and causes in some areas episodes of lightning storms. Other areas, however, are arid. Galileo, for its part, shows us another image of Ganimides, the only satellite of the Solar System with its own magnetic field, for the moment.

We have known that the Calisto satellite, full of craters, of Galileo's data, is covered in some places by a layer of fine dust. After the visit of the Voyager probes of 1979 we have seen that the surface of Io has changed. Scientists have found evidence that under the ice mantle of Europe there has been an ocean – still persistent apika – in not very ancient geological times.

Although Galileo's mission initially ended on December 7, 1997, NASA and the US Congress have decided to extend it until the last day of 1999. The GEM mission consists of three concrete objective steps: Campaign Europe (Ice), Periapsia (closest point of Jupiter)/Study of the water of Jupiter/Io Bull (cloud of charged particles in the form of a nozzle orbiting Io) (Water) and Campaign Io (Fire).

Campaign Europe

In 8 year-long spots, Galileo will look for more tracks over the ocean under the ice surface in Europe and try to decide whether the ocean is still present. Scientists will explore the surface in search of possible ice volcanoes or direct evidence of subsurface water. They will count craters to measure the ‘youth’ of the smooth surface of the satellite – fewer craters, more youth.

Galileo will analyze the European inner layers by measuring the gravity effects of the satellite, exploring the thickness changes of the ice layer and looking for possible depth indicators of the subsurface ocean. A flowing saline ocean can cause a magnetic field, so scientists will try to limit the generation of magnetic signals close to Europe.

Galileo will reach detail images and European atmospheric data, as well as polar regions. It passes relatively close to the surface, with a periapsia between 200 and 3,600 km. In this way, highly accurate images are obtained. Some images will have a resolution of 6 meters (the size of a truck! ). Through the representation in three dimensions, we will determine the height of the elements of the sufficiently flat European surface.

We will make a map of composition and distribution of ice in Europe with a resolution of 10 meters. We will look for potential contaminants in surface. Pollutants can be a consequence of the bombardment of comets and meteorites or have their origin within Europe.

Approaching Jupiter

Summarizing the periapsis, Galileo approaches Jupiter and is situated in the passage area of Io. In 1999, for six months and along four scars, taking advantage of the gravity of the attractions of Calisto and by means of the light measured of the directional rockets, will achieve the periapsis of Jupiter.

Your closeness to Jupiter will lead you to investigate details of winds and storms, including lightning storms that reach a huge altitude.

The water circulates vertically through the high layers of Jupiter, leaving some areas drier than the Sahara and others like the terrestrial tropics blai-blai. Drawing up the water distribution map and understanding its role in time on Jupiter can help to understand the rapid changes in time on Earth.

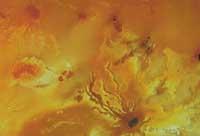

Once in each orbit, passing from ice to fire, Galileo will cross the Io bull. Galileo will measure the density of the sulfur currents that give off the volcanoes of Io and sodium and potassium extracted from the surface of Io by the particles driven by the rotating magnetic field of Jupiter.

Campaign Io

Besides being the closest satellite to Jupiter, Io is the most active body of the Solar System, with dozens of sulfur and silicate volcanoes. Io, on the other hand, is a mystery and with the last two orbits of the GEM you can learn a lot. In fact, Galileo will pass to 500 km and 300 km respectively of the area of Io.

Why did Io go back? It seems that scientists want to maintain suspense. It's not about that. Leaving Io's exploration for the end, the periapsis changes in Jupiter are minimized and there is more time left to perform a different scientific study. In addition, the probe receives less violent radiation from Jupiter. The radiation of Jupiter is stronger as it approaches the planet and has enough strength to kill man around Io.

Getting more than less

Taking into account the vision of NASA's lower cost space exploration, the design of MMG will allow for a low-cost, higher-risk mission with a concrete goal using a spacecraft that is already working. For the annual cost to be less than 15 million dollars we have moved to a minimum the operations of the spacecraft and the Earth. Engineers and scientists have automated everything they have been able to, moving the staff who will work 20% of the original mission.

Once the GEM is finished, Galileo will not issue any more scientific data, but it will circulate around Io until the radiation dies emitting data on his health. If you want to know the adventures of Galileo, in the web there is where.