About stereoscope

Why do the objects we see look like bodies and not flat figures? Although the image that appears on the retina of our eyes is flat, what happens for us to see the objects in three dimensions?

Different factors intervene in this problem. On the one hand, the different degree of brightness that the different parts of the objects receive gives us the idea of appearance. On the other hand, since the different parts of a body are at different distances from our eye, for us to have a clear image, the eye has to do an adaptation work, so since this adaptation is done with respect to a point of the body, with respect to a distance, that is, while we see that point completely clean, the rest, in some way, we will see it blurred producing a sensation of relief.

However, the most important factor in this process is that the image that each eye gives us on the same object is different. To check it just look at an object next to us, first with the right eye closed with the left and then with the opposite. The image that gives us the right eye is different from that of the left and make appear in our brain the idea of relief.

Now we will take on a single object page, therefore, on a plane, two drawn images, one as the real object that sees the left eye and another as the one that sees the right. In these images, if each eye only sees the corresponding image, instead of seeing two flat figures we will see a convex object. These pairs of drawings are observed using a special device called stereoscope. In the old stereoscopes the union of the images was obtained by mirrors, while in the present prisms are used convex. Therefore, although the basic idea of stereoscopy is very common, what is achieved is really surprising.

Natural stereoscope

However, stereoscopic images can be seen without the help of any device. For this it is only necessary to perform a special correction of eyes. The result obtained is equivalent to that obtained with the device (without increasing, of course, because stereoscopes also use to increase the image). The inventor of stereoscope, Wheatston, initially used the natural pathway.

Next we will follow a series of stereoscopic drawings, increasingly difficult and without any help, that allow us to look live. Some successful attempts must be made.

We started with those two black dots of the image. We will direct the view to the gap between the two, without moving and for a few seconds; meanwhile, we will make the effort as if we want to see an object behind the drawing. The points that we will see shortly will not be two, but four, which will occur. Finally, as the external points move away, the inmates will approach to join.

Once this is achieved, let's do the same with the following pair of images:

Once we get the sum of both, we are willing to do it with the following couple:

In this last unification we will see something like the inside of a pipe whose outlet is far away.

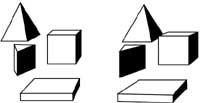

Once this has been obtained, as we have said, if we look at this other figure, we will see the geometric figures as if they were suspended in the air.

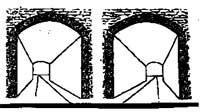

Or this will give us the interior image of a long tunnel.

Seeing these pairs of images as indicated is usually not very difficult. People with shortsighted and tired eyes should not remove the glasses and should do so as if they looked at any other image. However, it is advisable to move the drawing away or close it until the optimal distance of the image is achieved. All these attempts must be made with good clarity and not spend too much time on them so that their eyes do not tire.

View of giants

When an object is far from us (more than 450 m), the distance between our eyes cannot produce two different images in our two eyes. Therefore, the remote houses, the mountains or the landscapes seem flat to us, and all the bodies of the sky are at the same distance, although the Moon is much closer than the planet and these more than the stars.

Therefore, with objects over 450 m high, we lose the ability to directly detect the relief.

These objects are the same for our two eyes, since the distance between them of 6 cm is very small compared to 450 m. Therefore, being stereoscopic photos obtained in these same conditions, there is no feeling of relief in the stereoscope.

But this has a simple solution: distant objects must be photographed from two points that are more distant from the distance that separates our eyes. By looking at these two photos at once through the stereoscope, we will see things as if the distance between our eyes were much greater than normal.

This is the tail of stereoscopic photos of landscapes. In most cases we see them with enlargement prisms and the effect obtained is surprising.

Based on all this, we can achieve the same effect as with the camera using the “stereoscopic glasses”. These are formed by two tubes located at a distance greater than the one that separates our eyes. The image that each tube takes, after passing through several prisms, reaches our eyes. The sensation that is perceived when looking with these glasses is impressive: the distant mountains acquire relief, rocks, houses and boats are seen in space and not as if they were on a flat screen. Thus our landscapes would see the great giants.

These glasses are usually used by sailors, artisans and agriculturalists and usually carry a distance measurement scale (stereoscopic telemetry). The usual binoculars we use ourselves often, with a distance between objectives greater than between our eyes, give a stereoscopic effect.