Nobel Laureates 2011

Physiology or Medical Novel

Bruce A. Beutler and Jules A. Hoffmann, and Ralph M. Steinman

To the first two for "discoveries about the activation of intrinsic immunity" and to the third for "discovering dendritic cells and their function in adaptive immunity"

This year's Nobel Prize in Medicine will probably not be remembered solely for the merits of the winners, but because one of them will not be able to receive the corresponding prize for being dead. Ralph Steinman died three days before the Nobel Foundation announced the names of the winners. In fact, the rules indicate that the dead cannot be rewarded, but since he died after the decision to give him the prize, the Nobel Foundation has decided to make the exception.

Steinman dies with pancreatic cancer. He was diagnosed four years ago and has survived thanks to immunotherapy. This therapy is based on dendritic cells identified by Steinman for the first time.

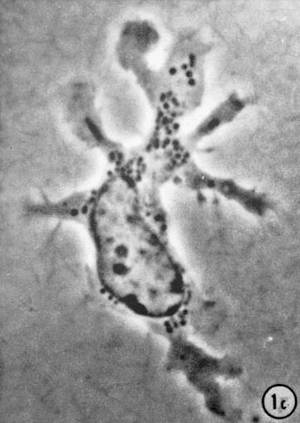

Steinman succeeded in identifying dendritic cells in 1973. He later discovered their function and demonstrated that they activate T cells. T cells develop an antisubstance memory that is essential in adaptive immunity. Steinman's research has therefore been key to understanding this type of immunity, and the Nobel Foundation has recognized it through the award.

The other half of the prize is Bruce A. Beutler and Jules A. It will be collected by Hoffmann researchers for their discoveries in the activation of intrinsic immunity. Although they will receive half a prize together, the work was not done at the same time.

The discovery that brought him the award that Jules Hoffmann made in 1996. He investigated how fruit flies are protected from infections; they were mutated flies, some of them with the mutated Toll gene. When he infected these flies he saw that flies were unable to launch protective mechanisms. He discovered that this gene is key in the immune system.

The discovery that Bruce Beutler made two years later, in 1998, was decisive for the award. He began investigating the PTS receptor that produces septic shock and discovered the mechanisms of septic shock and inflammation. They demonstrated that intrinsic immunity was similar in insects and mammals. He also opened the door to numerous investigations to study his own immunity.

Physics Novel

Saul Perlmutter, Brian P. Schmidt and Adam G. Riess

"To discover the acceleration of the expansion of the universe through the observation of remote supernovae"

The universe expands because Big Bang emerged in the explosion. But if it were a mere consequence of an explosion, that expansion would slow down over time. However, Nobel Prize laureates in Physics found the opposite, that the expansion of the universe is getting faster.

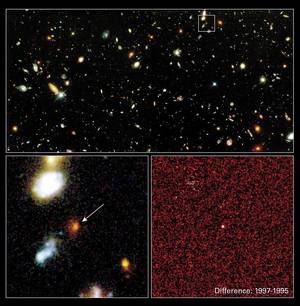

Perlmutter, Schmidt, Riess and other astronomers were surprised to find the acceleration. The result was two-way, as the winners were competitors. The first to find acceleration was Perlmutter in the Supernova Cosmology Project, and was later discovered by Schmidt and Riess in the High-z Supernova project, which will receive half the prize and the other half will be distributed by Schmidt and Riess.

Both groups observed type 1a supernovae -- white dwarf explosion -- to discover the limits of the universe. This distance measurement method was developed by astronomer Henrietta Leavitt in the 1920s, using stars to do so, but the stars of the universe border are not seen. They are too far away. Hence the study of the supernovae, an option that came in the nineties when there were powerful telescopes and accessible systems of CCD image sensors.

When this year's winners discovered that the expansion of the universe is accelerating, they thought it was a miscalculation. Riess, for example, told the blog Scientific notes from MIT that he had thought about calculations. "People like me don't make great discoveries." But there were no mistakes in the calculations. Many supernovae were observed and the fact that the two teams obtained the same result is true.

However, it is not known what accelerates expansion, although the culprit has a name: dark energy. Precisely, one of the main challenges of today's astronomy is to clarify what this dark energy is. According to all hypotheses, those who clarify will also receive at some point the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Chemistry novel

Daniel Shechtman

"by discovery of quasicrystals"

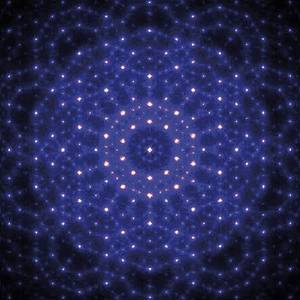

Quasicrystals, like crystals, are materials with ordered atoms, but this order does not have a repetitive pattern, as crystals usually have. They are currently known and synthesized in laboratories around the world. In the 1980s, however, Daniel Shechtman had to fight for this atomic organization he had just discovered, as crystallographs and physicists considered impossible. It was finally accepted and Shechtman's discovery represented a change in the very definition of crystals. Hence the Nobel Prize in Chemistry this year.

Shechtman himself was surprised to see a diffraction model that was considered impossible under the electron microscope. He studied aluminium and manganese glass. In particular, I tried to know which model the electrons were deviating when crossing this material. In fact, this deviation or diffraction of electrons shows the arrangement or distribution of atoms in the material.

Shechtman saw a ten-point diffraction model in a circle. In the International Picture of Crystallography, in the most important reference guide of crystallography, no crystals with this structure appeared. In fact, in subsequent analyses he concluded that the material had a symmetry of five orders, and it was impossible for the material containing that symmetry to be crystal, since it is impossible for that symmetry to exist and that the atoms were ordered by a repetitive pattern. Until 1992, however, this was the definition of crystals and the condition of being a crystal.

When he attempted to publish an article informing of the discovery, he immediately received a negative response. Even when he informed scientists crystallography experts of his discovery, they turned against him. The head of his research team came to ask him to leave the group. He had the help of physicist John Cahn and crystallographer Denis Gratias to publish the discovery of quasicrystals, a structure that gradually accepted experts. In 1992, the International Association of Crystallographs approved the following crystal definition: "any solid with discrete diffraction diagram".