Fossils of our corners

“When my friends ask me that they want to see fossils or some museum, they tell me about the footsteps of dinosaurs of La Rioja, Atapuerca, etc., but they do not know that in Bilbao there is an Archaeological Museum, in Vitoria the Natural Sciences Museum of Alava, or that in the Geopark, in addition to the rocks, you can see fossils,” says the Paleaintabitarte. “Also at the University, undergraduate or graduate students talk about paleontology referring to the external.”

Badiola is clear: “What we have here is not well known. And, of course, if not known, how will there be awareness about paleontological heritage.” The fact is that “there is more awareness with biodiversity, but less with geodiversity, and geodiversity is also part of natural heritage”, he claims.

With the aim of starting to change this situation, this year the book “Fossil Record of the Western Pyrenees” has been published. More than 40 experts have participated, including the book editors: Ainara Badiola Kortabitarte, Xabier Pereda Suberbiola and Asier Gómez Olivencia, professors and researchers from the UPV/EHU, and the last from Ikerbasque. “The objective is, on the one hand, to publicize the fossil record existing in the Western Pyrenees, Euskal Herria and its surroundings, and on the other hand, to tell how the management, conservation and dissemination of these fossils is done,” explained Badiola.

Although it is aimed mainly at undergraduate or graduate students, the book will be of interest to anyone who is fond of Paleontology, as it will find the most important paleontological and fossil deposits in the Basque Country, or how these fossils are managed and where they can be seen, among others.

Four hundred million years of history

The fossils found in the area of the Western Pyrenees tell a story of four hundred million years. It is the age of the oldest fossils that have been found, between 300 and 400 million years. Not many of those of that time, since the outcrops of the Paleozoic are very scarce in these areas. But there are some in Bortziriak, Aldude-Kinto and Oroz-Betelu. The marine invertebrate fossils of Devonian and Carboniferous are the most abundant, although some fossil vascular plants of rainforests have also been found.

The fossil record is not continuous, as it is also not a succession of nearby sedimentary rocks. “There are more palezoist materials – for example – Aiako Harria – but most of the materials are igneous or metamorphic, so there is not much chance of fossils,” explains Badiola. “Most of our fossils are from the Mesozoic and Cenozoic, and also within the Mesozoic, although there are sedimentary rocks from the Jurassic, most of the Cretaceous.”

Thus, “we have those ancient fossils of the Paleozoic and then jump to the lower Cretaceous 120 million years ago.” The sea level advanced and receded in the Cretaceous, but in general, in the northern slope of the Basque Country there are sedimentary rocks formed in the marine environment, and in addition to several microfossils, fish, mosasaurios, ammonite and other fossil mollusks abound. In the south, fossils of land animals predominate.

Dinosaurs in Laño

A major Cretaceous Superior site is located 25 km south of Vitoria-Gasteiz: Site of Laño (Treviño). “It is an international reference site, according to Xabier Pereda Suberbiola, rich in fossils and belonging to several groups of vertebrates. New species and genera have been identified in Lañón, and this is very important.”

A total of 40 species have been identified. Of them, a dozen are dinosaurs and the rest are fish, amphibians, lizards, snakes, crocodiles, flying reptiles, mammals, etc. “There is a huge diversity,” says Pereda.

Paleomagnetic studies have allowed to estimate traces in 72-73 million years. At that time the coast was located in the vicinity of Vitoria-Gasteiz, area of Laño that would constitute a relatively wide river and close to the coast.

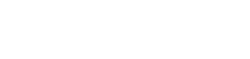

In this landscape lived, for example, the slender titanosaurs Lirainosaurus astibae. They were the ones who left the most: a hundred teeth and a hundred bones. Among the rest of the dinosaurs were a battleship, the ankylosaur; or other so-called ornithopods; and half of the species found are teropods, carnivores.

Among the new species found in Laño are, in addition to the lirainosaur, the Dortoka vasconica turtle, the Herensugea caristiorum snake, the Musturzabalsuchus buffetauti crocodile and the primitive mammal Lainodon orueetxebarriai.

There are other small deposits of similar fossils in the area. “In Izki Park, in the Corres area, for example, dinosaurs, crocodiles and turtles have been found,” says Pereda, “but it has nothing to do with the abundance and diversity of Laño. There is an extra concentration of fossils in Lañón.”

Time of mammals

The photo showing the Laño site was going to change radically, with massive destruction occurring between 6 and 7 million years later. Not only birds, but most dinosaurs would disappear forever. Among the survivors, mammals would be one of the most successful.

Although before the weather was quite warm, in the Eocene, even more so: “Some 56 million years ago it was a thermal maximum and almost all the world tropical or subtropical ecosystems multiplied,” explains Badiola. In this situation, the mammals were filling the ecological spaces released by the dinosaurs. “At the time of the dinosaurs there were also mammals, but most were very small. During the eocene, mammals will increase in size and diversify and expand noticeably. Many groups of current mammals will appear.” For example, journalists, the current group of horses, tapes and rhinoceroses; or artiodactyls, the group of cows, sheep, pigs, camels, etc. Also real primates or euprimates.

An important site of this time is located in Zambrana (Álava) (Place of Geological Interest). The landscape that is built with the remains found is the marshy edge of a lake about 37 million years ago. 26 species of vertebrates have been found; amphibians, crocodiles, turtles, lizards, marsupials, primates, rodents, carnivores and, the most numerous, perisodactilos and artiodactyls. “The journalists and artiodactyls had a much greater diversity than the current one and were very different,” says Badiola. “For example, in many current artiodactyls it is customary to have horns, in those times they had no horns”.

The diversification of mammals was not limited to land. Some also went to the water. Cetacean fossils of the time have not been found in our environment, but siren (of the current group of manatees and of those we have). Highlights are the discovery of the site of Castejón de Sobrarbe (Huesca). Sirens, like whales, have been transforming and losing all four legs throughout evolution. The current manatees and dugones have in front of the lethed extremities and the two rear ones are missing. As the mermaid discovered in Huesca, cardieli de Sobrarbesi, still had all four legs. “In the world few primitive four-legged Syrians are known and Huesca is the best collection of fossils. That’s why this discovery is very important,” says Badiola.

Also in Navarre, in Uztarroz, Ardanaz and Urbasa-Andia, vertebrae and ribs of the mermaids have been found. And the whole environment was the sea at that time. The Pyrenees mountain range has not yet risen. The Iberian and European plate began to join, but between them there was still a sea branch. That is why in Navarre, in Huesca, and also in Catalonia, fossils of the marine environment appear, among them sirens”.

In this situation, “the fauna present in the Eocene has been quite endemic,” says Badiola. “Europe was an archipelago where the Iberian peninsula was an island. For example, many of the perisodactyls found in Zambrana, such as Iberolophus arabensis or Pachynolophus zambranensis, are different from those found in France, Switzerland or Germany.”

At the end of the Eocene, the climate cooled and the tropical world ended. The closed forests were replaced by more open landscapes, in the form of savannas. In addition, alpine orogeny caused Asia and Europe to be connected, and the fauna that entered the Asian side caused the disappearance of many pre-existing animals. The remains of this time, about 20 million years ago, have been found in the Bardenas, among others. “The scenario changed radically,” says Badiola, “and their descendants will be the ones we will later have in the Quaternary, which make us better known. But Eocene was another world.”

Jaguars in Zierbena

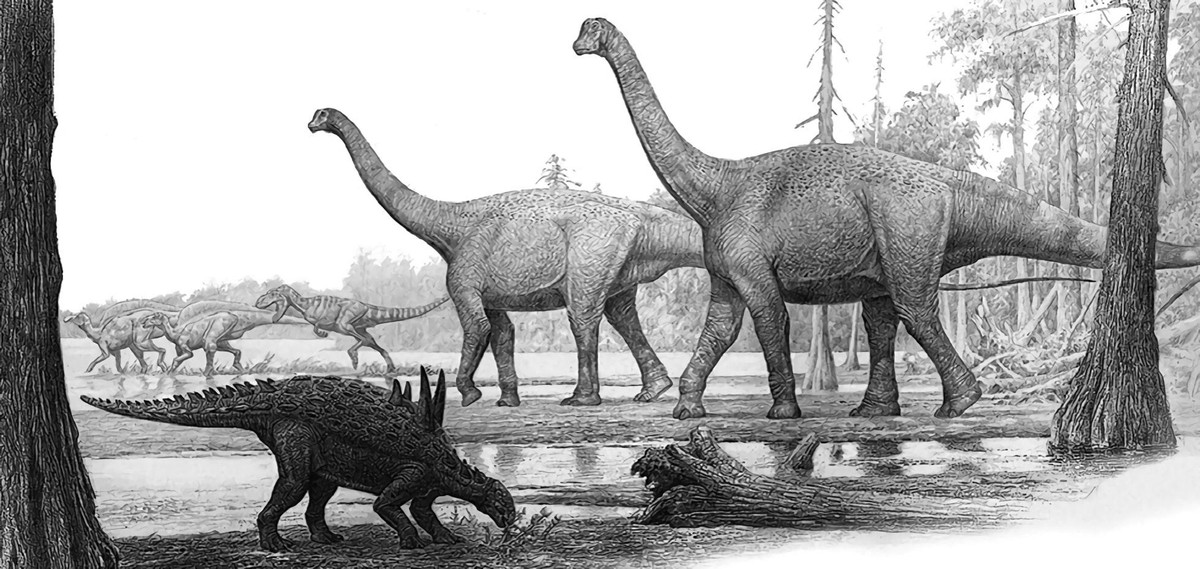

The oldest fossils of Quaternary macromammals present in our corners date back to 500,000 years, coming from the site of Punta Lucero (Zierbena, Bizkaia). “We don’t know very well what this area was like at the time,” explains Asier Gómez Olivencia. “We don’t know if we are in a glacial or interglacial moment. But what we know is that some of the mammals that lived at that time no longer appear in the fossil record of Euskal Herria.”

In Punta Lucero there are three very special species that do not appear anywhere else. One of them is the European Jaguar, Panthera gombaszoegensis, something bigger and stronger than the jaguar that lives today in America. The second is Canis mosbachensis, ancestor of the current wolf, somewhat minor. And the third, the saber-toothed tiger, Homotherium latidens, the size of a current lion.

In Punta Lucero there are also fossils of more mammals: giant deer, common deer, bison, rhinos, uros, etc. “But these are also found in other deposits,” says Gómez Olivencia. “These three species make Punta Lucero so important. And also chronologies; comparing with other deposits in the area, at least 200,000 years old are the mammals of Punta Lucero”.

The site was found only in 1987 by Iñaki Lebanon, a quarry used for the works of the Port of Bilbao. And probably most of the deposit was destroyed in the quarry.

Another important Quaternary mammal site is located in a quarry: Koskobilo (Olazti, Navarra). Fossils of different chronology have been recovered from the quarry. “It is the only site with hippopopotamus in Euskal Herria. In Europe the hippopopotamus disappeared 125,000 years ago, so the hippopopotamus gives us a minimum age and also tells us that it was a hot time”, explains Gómez Olivencia.

Two other unique species found in Koskobilo are the Tibetan bear and macaque. “The Tibetan bears entered and disappeared into Europe twice in the Pleistocene. They are very rare fossils in this extreme of Europe” says Gómez Olivencia. Macaque has also been found in Lezetxiki. And although initially estimated at 75,000 years, the most recent studies have shown that it can reach 170,000 years. “Surely the macaques would live in that warm moment, where there were hippos, Tibetan bears, rhinos, deer, beavers, etc.”

Human remains

At that time, in these corners there was another species closer. “Neanderthals were here for at least 200,000 years until they disappeared some 40,000 years ago,” explains Gómez Olivencia. In Lezetxiki, Axlor and Arrillor have found their fossils. Not many, a jet and a few teeth. “They don’t provide much information. However, the archaeological record does tell us that their cultures were changing. It is observed that in the same place, at different times, they hunted different species and cultivated the different flint. They were Neanderthals from different cultures.”

Our species was introduced in Europe about 45,000 years ago. “We don’t know if they met the Neanderthals here because there is little information,” says Gómez Olivencia. Sapiens fossils have been found in five deposits. “They are very few fossils. But there are unique sites of interest such as Santa Catalina (Lekeitio). It is a cold moment and many reindeer bones have been found. Also the signs of fishing and some birds they hunted, like the giant moose”.

These sapiens, in addition to fossils and utensils, left other information about the fauna of the time: rock art. In this case, however, what rock art tells does not exactly match the history of fossils. “Above all they drew horses and bison,” says Gómez Olivencia, “but in the deposits (as in Santimamiñe) it is observed that they mainly hunted deer. So, if rock art is a reflection of their imaginary, their imaginary and the hunters had nothing to do with it. In short, these human beings were like us, because we are the same species.”