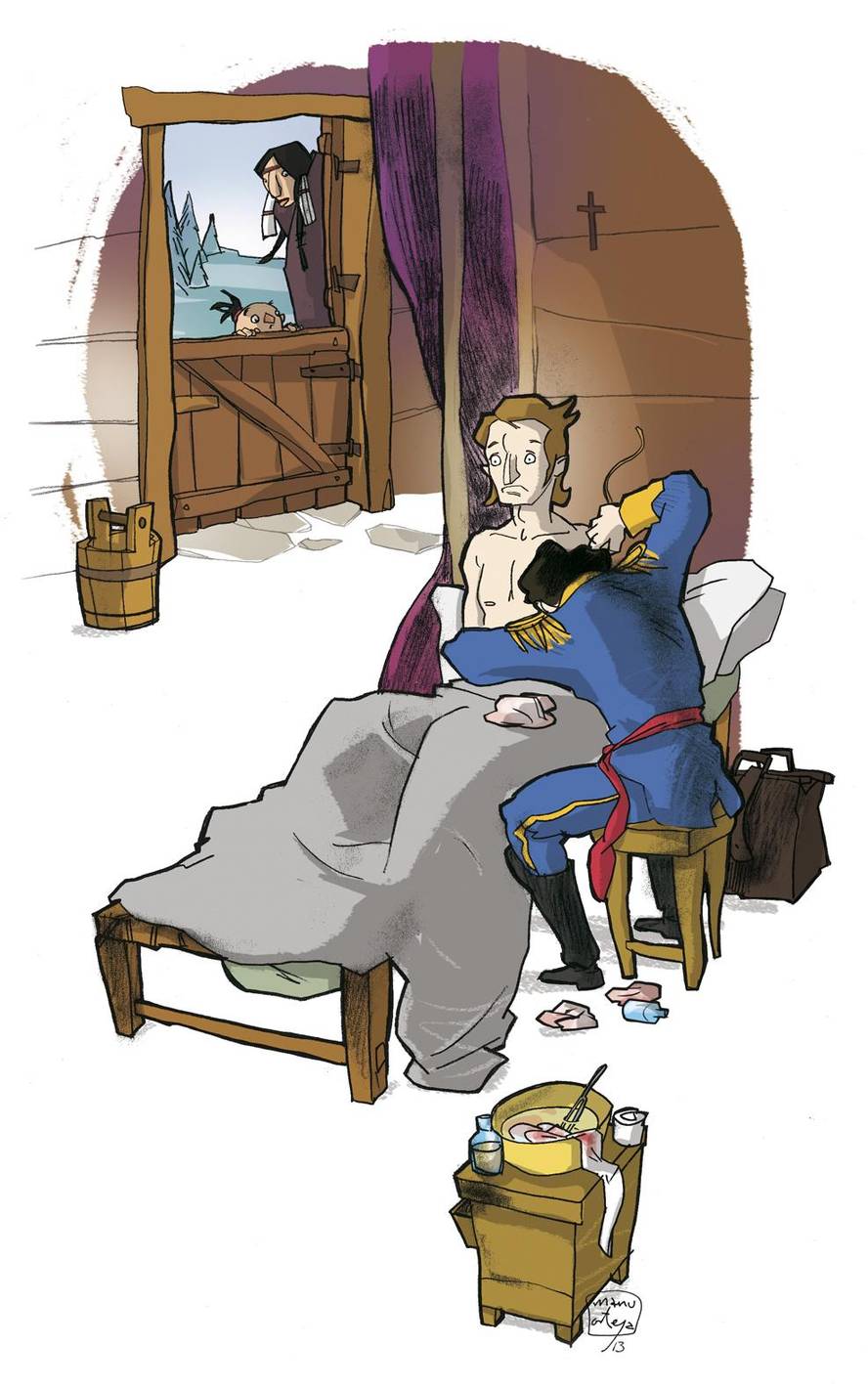

Doctor Beaumont and stomach of St. Martin

He took a piece of raw beef with a little salt and tied it with a thread. He took the other side of the thread and put it into the hole. One hour later, he threw the thread and checked how the flesh was. An hour after putting it back into the hole and again... And then with the fat pig... In the fifth hour St. Martin was put in the pain of the gut and Dr. Beaumont had to remove from the stomach the remaining human part.

The next day, St. Martin still had ingestion. But indigestion, indigestion, Dr. Beaumont did not waste the possibility of carrying out these experiments. Nobody ever did it.

The three-year accident. On June 6, 1823, the young Canadian Alexis Bidagan was nicknamed in St. Martin, Mackinac Island. The American Fur Company had just started working as a voyageur, which consisted of transporting beaver skins with canoe. That morning he was in the company's warehouse, and next to him was a member with a shotgun loaded for ducks. He escaped the shot and the pellets caught St. Martin. He fell to the ground on the fire of the shirt.

The doctor came along the way among the crowd around the wounded man. The only doctor on the island; Dr. William Beaumont. The wound under the left chest broke with ribs 5 and 6, a piece of lung, and the diaphragm. Breakfast came out of the perforated stomach. "He won't live 36 hours," the doctor said.

Beaumont made every effort and St. Martin began to recover. For the first 17 days, everything he ate came out of the wound. But gradually the intestines began to work and by the fourth week I could eat normally and do digestion.

However, it took him to complete it. In the fourth month, Beaumont was removing the pellets from St. Martin's body. In the tenth month he noted in the notebook that the wounds were almost healed, but that the patient was still completely disabled. Then, the authorities decided not to pay more attention to St. Martin and send him to his hometown. However, Dr. Beaumont feared that there would be too many trips of about 2,000 kilometers and welcomed them into his home.

The wounds were healed, but the hole remained, a hole that went directly to the stomach, a new anus. "It was the size of a shilling and the food and drinks were poured by it, if they were not closed with plugs, compresses and veins," Dr. Beaumont described.

Beaumont hired St. Martin as an assistant. But I wanted more for that. In an article published in The American Medical Recorder in 1825 he said: "This case is a great opportunity to investigate gastric fluids and the digestive process. It would not produce minimal pain or discomfort, removing a little fluid every two or three days, otherwise it comes naturally in relatively high amounts. And it would also be easy to introduce certain digestive substances and observe them during the digestive process."

He began to experiment on August 1, 1825. He brought him all the cooked, raw meat (with salt and without salt), fat pork, canned meat, old bread, cabbage... Once fasted for 17 hours, the temperature of the stomach (38ºC) was taken, extracting the gastric juices. Subsequently, in the test tube full of gastric juice (maintained at 38ºC) and in the stomach of St. Martin the same amount of meat was placed. The stomach digested in two hours and the test tube needed 10.

St. Martin was not always interested in experiments. It was not pleasant to do those long periods of fasting, or to remain motionless during the hours while the doctor introduced and took food into his body -- in addition, there were often pains of gut, diarrhea, etc.-. He even refused to keep test tubes full of water in his armpits. It was true that he was indebted to the doctor who saved his life, but... Seeing the opportunity he left for Canada.

There he married and had two children. A poor family, Beaumont managed in 1829 to convince St. Martin to reexperiment in exchange for welcoming the whole family into his home.

Beaumont showed that digestion was a chemical and non-mechanical process, as I most often thought. He saw that gastric juices needed heat to digest, that vegetables are harder to digest than many other foods, and that milk is drained before digestion begins. He studied the influence of time and concluded that St. Martin was angry from time to time and that anger made digestion difficult. Two years later, the family took the canoe and went from Wisconsin to Montreal.

In 1833 he published Experiments and Observations on the Gastric Juice and the Physiology of Digestion. There he collected 240 experiments with St. Martin.

This work brought fame to Beaumont. But also criticism. Some believe he did not knowingly recover St. Martin's hole. And that controversy would ignite more strongly in another 1840 affair. A politician attacked a newspaper editor on the street because he was not treated well in the newspaper's editorials. He hit the head with an iron stick and the editor became impassive. Beumont was one of the surgeons chosen to treat the editor. He decided to drill the skull to remove the pressure. The editor died and Beaumont was charged with murder alleging he struck because he wanted to see what was inside as with St. Martin. The judge blames him and imposes a fine on him.

Beaumont would spend his entire life trying to convince St. Martin to do more experiments until his death in 1853, slipping on icy stairs. For his part, St. Martin falls into the hands of a scammer posing as a doctor. And he toured the cities like a circus animal.

In 1879 he wrote to the son of Beaumont: "I've started to age and I've been sick in the last six years and I'm not going to hide that I'm very poor [...] I'm suffering a little with my gastric fistula and my digestions are worse than ever..." He died the following year, at 78. The family expressly left him uncomposing his body before being buried so that no one would be tempted to experience more.