Times of light

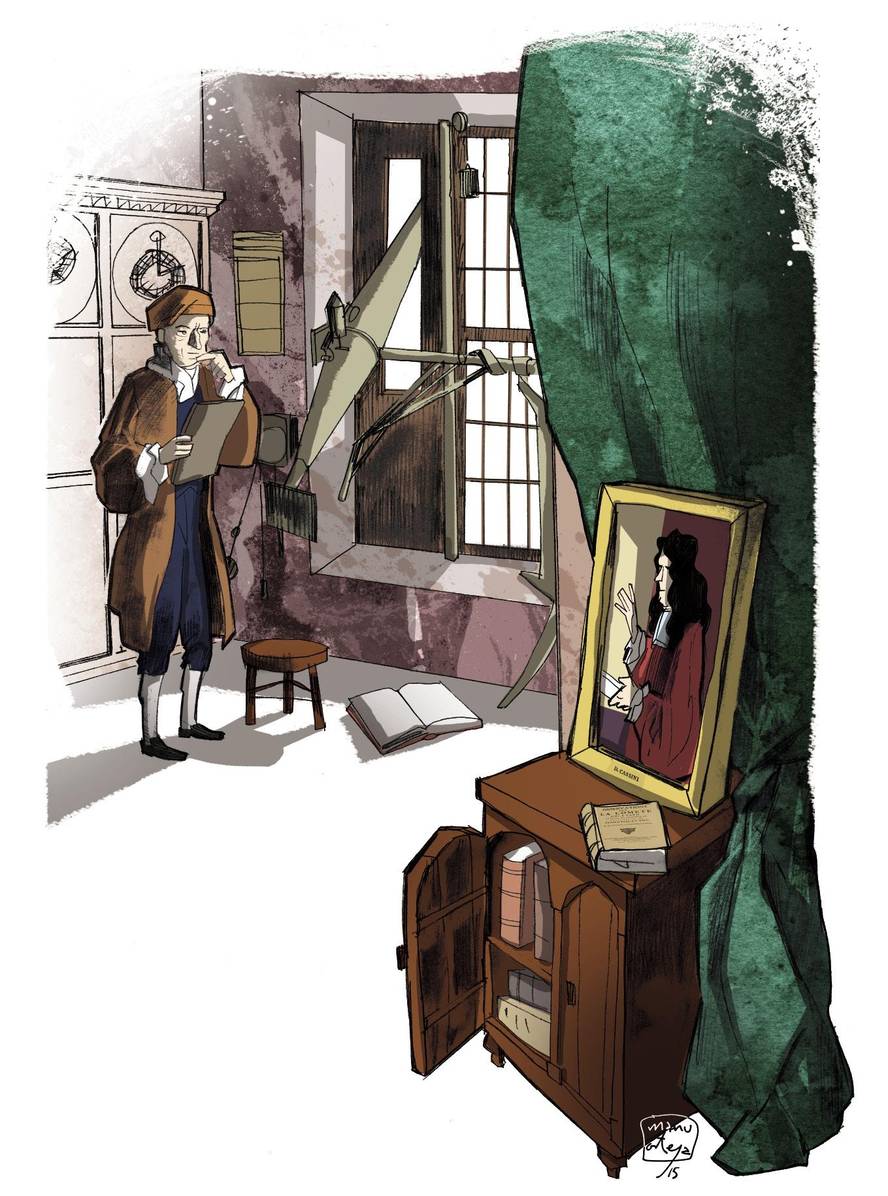

“What if the light really took a while to get from Jupiter?” Cassini and Rømer sought an explanation, as they could not understand why Io's eclipses sometimes occurred sooner than they expected and later. And that question of light could explain it. But then did the light end with a finite speed? Cassini dismissed this idea. Rømer advanced. He told it at the Paris Academy of Sciences in September 1676 and published it at the end of the year. They paid little attention to the Danish astronomer. Most were clear, like the great Kepler and Descartes, that the speed of light was infinite.

It was a debate of many centuries. At the time of the Greek philosophers, Enpedokles was the first to propose that light had a finite speed. In Baia the vision of Aristotle was the most widespread: “light is not a movement.” Later, Heron of Alexandria defended that the movement did, but that it had an infinite speed, arguing that we can see stars so far away as soon as we open our eyes. At that time it was believed that light came out of the eyes.

XI. In the early 20th century, Ibn al-Haytham demonstrated that the light emitted by a light source is reflected in objects in all directions and that the light reflected by objects is seen when it enters the eyes, and not on the contrary through the rays of light emitted from the eyes. Al-Haytham believes that light had a finite velocity and, moreover, variable depending on the density of the matter it crosses. XIII. In the 19th century, Roger Bacon defended, based on the writings of al-Haytham, the finite speed of light.

But XVII. At the beginning of the 20th century, Kepler reproposed that the speed of light was infinite, seeing that emptiness was not a clear obstacle. In his opinion, the light emitted from point A could be seen simultaneously at point B, although between the two points there were several miles of billions. In addition, the great philosopher and mathematician Descartes shared Kepler's ideas and firmly defended his arguments.

Galileo tried to shed some light on that debate. He thought there should be some way to empirically demonstrate this question. And in 1638 he proposed an experiment: In both hills would be placed a person with a flashlight covered. One of them would discover the lantern and, seeing its light, the one on the other hill would do the same. The first would measure the time since the flashlight had been covered until it saw the light of the second. So they would know if the light had a finite speed. It seems that Galileo tried it, and in 1667 the researchers of the Accademia del Cimento of Florence also did the experiment, but they were not able to draw conclusions.

Cassini and Rømer did see that from Io's observations it was deduced that the light took a while to reach Earth. In fact, another question was being investigated. Galileo discovered in 1610 the four moons of Jupiter and later proposed that these moons of Jupiter could be magnificent clocks to calculate their length. This required precise measurements of the orbits of the moons.

Rømer joined this after completing his studies at the University of Copenhagen. In 1671 he spent several months supporting the French astronomer Jean Piccard on the Danish island of Hven, at the Uranienborg observatory of Tycho Brahe. They observed the eclipses of Io. It was a way to measure the length of your orbit. Seen from Earth, Io hid behind Jupiter whenever it formed an orbit. Therefore, the duration of Io's orbit was between the eclipse and the eclipse.

The following year, Rømer traveled to the Paris Observatory to collaborate with Giovanni Cassini. Cassini had also been observing Io's eclipses for years. Cassini and Rømer realized that the time between Io's eclipses was rare. They knew that the duration of Io's orbit had to be fixed, always the same. So it was also of our Moon, and of the rest of the moons and planets. But the data were variable. And they also realized that the distance between eclipses was greater when the Earth moved away from Jupiter and smaller when the Earth approached Jupiter.

But how could the Earth's orbit affect Io? You could not. The only explanation was the speed of light. If the light took a while to get from Io to Earth, when the Earth was away it would take longer, so the eclipse would look later. Cassini was the first to give that idea. In August 1676 he wrote: “The difference suggests that light takes time to get from the satellite to us.” But Cassini was not convinced and totally rejected the idea, thinking that they would be errors of observation or that there would be another reason.

Rømer advanced. Analyzing the data well, he calculated that it took 22 minutes to cross the Earth's orbit. He did not calculate speed; in short, the important thing was to prove that he had finite speed. Christian Huygens took the idea enthusiastically. And based on Rømer's work, he did the calculations: 230,000 km/s (76% of what is currently approved).

Bibliography:

Bobis, L. and Lequeux, J.: Cassini, Romer and the velocity of light. Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage 11(2), 97-105 (2008)

Dabrowski, J.P., Snyder, G., Marschall, L.: “Jupiters moon and the speed of light”. Project CLEA (Contemporary Laboratory Experiences in Astronomy), Gettysburg College

Júncher, D.: “Ole Rømer” Niels Bohr Institute, Univesity of Copenhagen

Nissani, M.: “A Case History in Astronomy and Physics: The speed of light” Wayne State University

"This entry participates in the 3rd #Culture Scientific Festival"